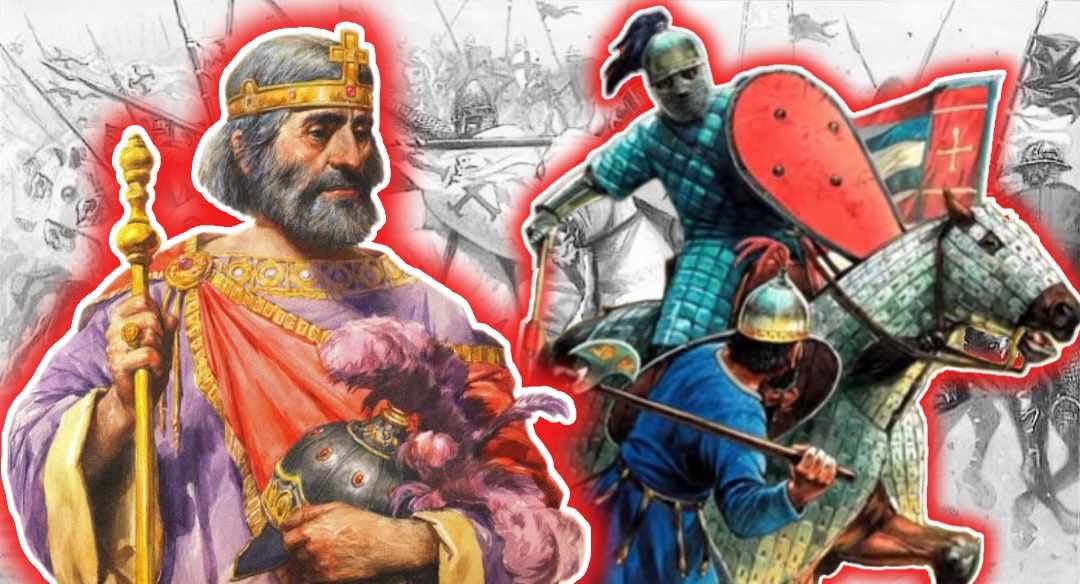

Heraclius and the Byzantine Proto-Crusade

The Byzantine-Sassanian War of 602-628 as the precursor to the Crusades.

Introduction

The Byzantine–Sasanian War of 602–628 is one of the great dramas of history. Though little known in the West, it could be argued that the religious fervor of both sides during the conflict makes this the first Christian Crusade. This essay seeks to solidify the status of the Byzantine–Sasanian War as the inaugural Christian Crusade and to delve into the Eastern Orthodox notion of Divine-Human Symphonia. By examining how this symphonia manifested itself in Byzantium’s wars, we can dismantle modern misrepresentations of religiously motivated warfare.1

A Cosmic View of the Conflict

When the pious Emperor Maurice, a brilliant general and emperor, attempted to reduce soldiers’ pay,2 the Roman Army murdered him and his family, replacing him with the soldier Phocas. The Sassanid Persian king of kings, Khosrow II, using his friendly relations with Maurice as a pretense for war, invaded Byzantium in 602.

While the murder of Maurice may have been Khosrow’s justification for war, it was also a result of Rome’s own sinfulness - both for allowing the emperor to be murdered and for their own descent into immorality. The Romans themselves largely recognized this to be the case, and certainly one cause doesn’t negate the other.

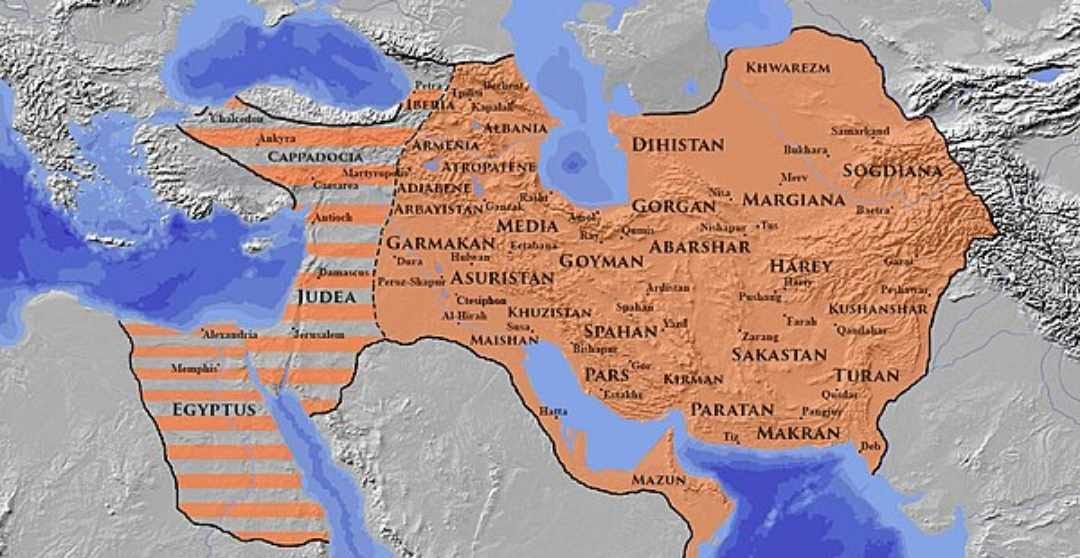

War with Persia was not new, the two had been going tit for tat since the days of Julius Caesar. It should come as no surprise that two large empires, both seeing themselves as the height of human civilization, bordering one another would come to blows. This was usually limited to proxy wars, skirmishes and raiding along the frontier.

The war of 602-628 was different, this was a winner takes all conflict - one which would exhaust both empires.3 After their initial victories, the Persians set out to eradicate the East Roman Empire

Heterodox sects - in schism with the Church since the council of Chalcedon4 - and Jews across Syria and Palestine joined the Persians, assisting them in gaining entrance to key cities. The Persians even marched on Chalcedon, sacking the city in sight of the Theodosian walls. This breakthrough to the heart of Byzantium happened only a year after Heraclius had married his niece, reinforcing to many that this was Divine retribution for the sins of the empire.

In early 614, Jerusalem fell after a three-week-long siege. The Persians set fire to the Holy Sepulchre, murdered 34,000-43,500 Christians, taking the Patriarch Zacharius and 30,000 Christians into captivity. Worst of all, they seized the True Cross, taking it to the Sassanid capitol of Ctesiphon. The Romans began to fear that the Persians would conquer all of Christendom.

“You say that you trust in your God. Why has he not delivered out of my hand Caesarea, Jerusalem, and Alexandria? And shall I not also destroy Constantinople?… Do not deceive yourself with vain hope in that Christ, who was not able to save himself from the Jews, who killed him by nailing him to a cross. Even if you take refuge in the depths of the sea, I will stretch out my hand and take you, whether you will or no.” - Khosrow II, Letter to Heraclius

Deus adiuta Romanis

Heraclius and Sergius,5 Patriarch of Constantinople, were of one mind as to what was needed to turn the tide of the war: the empire must repent and turn to Christ. The people gave up all luxuries, the theater and carnivals6 overnight, men rushed from across the empire to volunteer for the army and return the True Cross to the Holy Sepulchre.

But the imperial treasury was empty. Understanding the weight of the situation and seeing the sincere repentance of the people, Patriarch Sergius had all the gold - aside consecrated items - stripped from the churches of Byzantium, melted down, and handed over to the treasury.

This allowed Heraclius to rebuild and refine the Roman Army, focusing on discipline and mobility. Heraclius led a brilliant series of campaigns deep into the heart of Persia. The Persians, after years of using Heraclius’ armies as doormats, were shocked by his sudden fearlessness and strategic brilliance. In the end, all Roman territory would be restored and Khosrow II killed by his own nobles.7

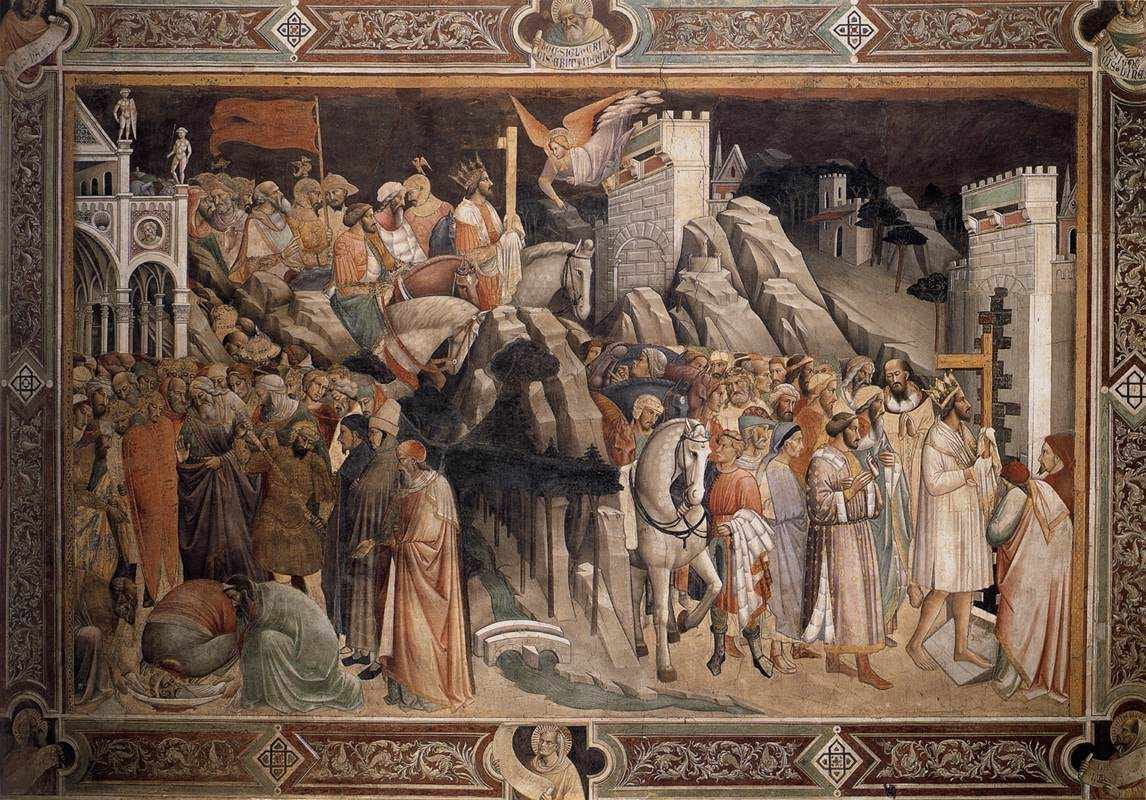

The Triumph of the Cross

After retrieving the True Cross Heraclius set out to return it to the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem. When he approached the gates of Jerusalem in a grand procession, Heraclius dismounted his horse. Removing his royal tunic and shoes, he carried the most sacred relic of Christendom on his back to the Holy Sepulchre to by the jubilant shouts and cheers of the now free Christians of Palestine.

As he approached Constantinople the people of the city rushed out of the gates, laying palm leaves before the army, singing psalms and hymns. Patriarch Sergius met the emperor at the gates to the city, greeted the emperor with the holy kiss, blessed the army, and led them to the Hagia Sophia, where a service of thanksgiving was offered to Christ for victory over the fire-worshippers. One can only imagine what it was like to have been there.

Looking at the key events of the conflict and the narratives which have come down to us, the parallels with the later Crusades are clear. William of Tyre - the famed historian of the First Crusade - recognized this, calling the Byzantine-Sassanid War the first of the crusades, even amending its history to his chronicle of the crusades.

The Orthodox conception of Divine Human Symphonia

I heard the voice of the Lord saying ‘whom shall I send, and who will go for us?’ Then I said, ‘here I am, send me.’ - Isaiah 6:8

To understand the theological context of the Byzantine–Sasanian War - as well as modern misconceptions of holy war as a mere exploitation of religious feeling - we have to turn to the Eastern Orthodox conception of Divine-Human Symphonia. This term encapsulates the harmonious cooperation between God and man in time. Symphonia is not so much an active partnership on an equal footing - as it is often misconstrued - but God working in the world through man’s cooperation with the Divine Will.

Symphonia is deeply rooted in the Eastern Orthodox worldview and understanding of salvation history - as we see it play out in Scripture itself - where the divine plan unfolds in history through a collaboration with human agency.

We can see this conception incarnated in the symbol of Byzantine power: the double-headed eagle. Each head of the eagle is crowned and above the two is a single, larger crown.8 The two heads represent the Empire or Oikumene9 and the Church. These work in concert to guide the people of the Orthodox Roman Empire - symbolized by the body of the eagle - under the larger crown of the King of Kings, Christ. The job of the emperor, therefore, is to assist and defend the Church in its salvific mission, to reflect Divine justice, mercy, charity, etc.. on earth, and to protect Christians around the world.

This notion of God ordained rulership is not a new concept invented by the Church, but a reflection of what we see in Scripture. For the Orthodox, there is no gulf between the world of Scripture and the world of today. Just as God ordained rulers such as Joshua, Solomon, and even Nero - as St. Paul makes clear, and as Christ Himself confirms - so too does He continue to do so after Pentecost.

In the Orthodox conception there is no separation placed between the spiritual and secular realms, the two are always considered together, working together. So, religious motivations cannot be so easily cast aside as modern scholars would lead us to believe.

The Rise of Islam and its impact on Christian conceptions of warfare.

The strategic victories under Heraclius weakened the Sasanian Empire significantly, setting the stage for its eventual capitulation to the Arab forces who would go on to establish the Islamic Caliphate.

As the Islamic Caliphate spread across the Holy Land and Egypt it quickly became apparent to the people of Byzantium that these were not mere sectarians, but a foreign faith aimed at the destruction of Christianity.10 The Roman Emperor in Constantinople was the Defender of Christendom, and universally recognized as such both in the Medieval West, and by their enemies. This was not a mere theory, but a daily reality for Romans. Many Western knights, hearing of the desperate struggle in the East, set out for Constantinople and were enrolled in the Roman Army in auxiliary units.

In the tenth century, the Emperor Nikophoros Phocas would ask the Patriarch of Constantinople to canonize all Roman soldiers who died fighting the forces of Islam as martyrs. Much to the dismay of Nikophoros and the thematic armies, the Patriarch refused. Among the frontier armies of the empire, fighting a generations long war against Islam, the notion of family and friends killed in battle being martyrs was quite common - and certainly a source of solace.

While this expression of popular piety along the frontier was formally rejected by the Churches, we can see here the seeds of Pope Urban's promise of absolution to Crusaders. It’s likely this concept was brought West by the many Western knights returning home after having fought and lived alongside the thematic armies and Tagmata. They would not bear fruit until the emperor Alexios Komnenos - himself a frontier general - went West to plea with the Pope for assistance in retaking Asia Minor from the Muslim Turks.11 This promise of absolution in exchange for bloodshed gave warfare a sacramental character in the West, giving rise to the warrior-monks young men of European descent have idolized ever since.

Divergent conceptions of Holy Warfare

Whether or not Christian soldiers killed in battle against non-christians were to be counted as martyrs - and the status of killing in warfare in general - is the real line of demarcation between East and West. The positions taken reflect the history and culture of East and West up to the beginning of the Crusades.

For Orthodox Byzantium, all men were created in the image of God and to kill a human being was not to be glorified. War was the duty of the State, a burden which men took upon themselves out of love for their kin and country, and for this reason the Church absolved killing in war out of economy.12 The blessing of soldiers and their weapons with holy water - a practice which continues to this day in Orthodox nations - is done not so that they would kill as many of the enemy as possible, but that the Lord would protect the army and grant them a speedy victory, ending the bloodshed as quickly as possible. The Church was to pray for a speedy end, that God’s will would be done, and to offer healing to the souls burdened by the killing of another man.

Things were different in the West. When Old Rome fell, Western Europe was left with an immense power vacuum. The remaining Roman aristocracy, with their large estates, became local centers of power and fought one another for land and titles. Being the only institution capable of doing so, the Church of Rome stepped into this power vacuum, taking on ever more secular functions as time went on. Bishops became lords, leading armies and law courts.13 Over time, Rome’s doctrines adapted themselves to the harsh reality of life in Western Europe - and its need for ever more secular authority. When the call from Pope Urban came, these many petty kings and nobles who had been killing rival Christian factions their whole lives, saw a chance to atone for their heinous acts. Urban’s sacramentalization of warfare was in this sense essential to launching the Crusade.14

The consistent stability of the state in Constantinople, by contrast, allowed the Eastern Churches to avoid involving themselves too much in the affairs of government. When warrior monks and bishops - many with vast land holdings and secular titles - appeared in Byzantium, the Orthodox were scandalized. There are accounts of Byzantine officials and citizens refusing to allow Western clergy and monastics carrying swords to even enter eastern ports. Westerners for their part found Roman men of the East to be effeminate, due to the lack of warrior ethos amongst the Roman elites of Constantinople.15

The pronounced differences in the political, social, and cultural experience of the Germano-Latin West led them to adopt a view of warfare which sharply diverged from that held by the Greco-Roman East, and earlier Western Christendom. Many of the late Roman emperors - especially of the Komnenian and Palaiologan lines - greatly admired the Western knights and attempted to adopt their conceptions of holy war and martyrdom. But the clergy and people of the Orthodox East refused to follow the ideological whims of the Constantinopolitan Court and maintained the same understanding of warfare against non-christians which they always had. This view outlived Byzantium and remains the Orthodox position.

Conclusion

The Byzantine–Sasanian War marks the first time a military conflict is expressed as a war for the survival of Christendom itself, because it was precisely that in the eyes of the Christian Oikumene. While the historical context and specific religious dynamics may differ, the echoes of Heraclius' campaign resonate strongly in the motivations and actions of the Crusaders. These realities more than qualify it as the first of the Christian Crusades. Crusader ideals, in essence, departed from Orthodoxy and built upon the popular piety of the Roman frontier.

By exploring the symphonic relationship between the divine and the human, we see that Byzantine rhetoric about the war was not novel, nor an evolution of doctrine, but the normative understanding of human affairs and the arc of history. The scope of the conflict and targeting of religious sites by the Persians simply drew the Byzantine’s symphonic worldview out in a way not previously recorded in historical chronicles. The novelty is therefore found in the circumstances, not the doctrine and rhetoric. To say this was a novel concept or marks a shift in how the Byzantines saw themselves, as some mistakenly claim, is an argument from silence.

These misrepresentations typically state that “holy wars” were never truly a Christian conception, but that secular institutions sought to exploit popular religious fervor for secular aims. This narrative is, unfortunately, promulgated by Evangelical Christians as often as it is Atheists.

Due to inflation and budgetary concerns, Maurice wanted to reduce soldiers pay. In reality, he had a full treasury, but after the post-Justinian turmoil, he wanted to set his successors up for success. This proposed pay reduction, combined with ordering his army to winter beyond the Danube, resulted in rebellion. Their chosen emperor Phocas led a brutal reign of terror that saw the empire fall into complete chaos. When Heraclius finally became emperor the army, ironically, willingly accepted a much more substantial pay cut.

The sheer scope of the war decimated the populations and economies of both empires. At the start of the war, immense rains hit Arabia, vastly increasing crop yields and the birth rate along with it. During this time, Mohammad had his revelation. By the time the two empires were exhausted, a swollen Arabia would burst out into imperial lands, wiping out Persia and the wealthiest provinces of Byzantium.

The Council of Chalcedon was a battle against a novel doctrine emerging out of Egypt claiming that Christ had one nature (monophysis/miaphysis). The council upheld the Orthodox doctrine of Christ having two natures (diaphysis), a divine nature and a human nature united in one hypostasis. Much of Syria and Egypt had fallen to this monophysite heresy. The monophysites then aided the Persian invaders - and later Muslims.

Patriarch Sergius would later help to formulate and promulgate the heresy of Monothelitism along with Heraclius and the Pope Honorius of Rome. Sergius and Honorius would later be condemned as heretics by the Sixth Ecumenical Council - though modern Roman Catholics try to skirt around this inconvenient fact. Tragically, they both died as unrepentant heretics.

Theaters in this context are erotic shows, essentially strip club/brothels. The carnivals spoken of are not like modern carnivals; these were festivals - which most saw as an innocent cultural heritage - containing acts of pagan devotion from old times. These were done away with.

We’ll save the narrative of the war itself for another time.

Some versions of the double headed eagle will show one single crown above the eagle. This is meant to give the same impression of Christ being the authority over both heads of the nation.

Oikouménē or οἰκουμένη: meaning “inhabited world” or “universe/universal.” this expresses the self-image of the Byzantine Romans, their empire and church, as being itself the totality of the world under Christ. Outside of this oikumene were non-christians, those still outside the Kingdom of God - in other words: barbarians. This concept didn’t necessarily limit itself to the borders of the empire. Kievan Rus was considered part of the Oikumene, as was Georgia, Italy, etc… the entire communion of the Orthodox Catholic world.

Many modern scholars try to claim this is not the case, that the Muslims were tolerant of Christianity, merely levying taxes on them. We can say that for the first generation or two - after a show of force of course - fear was supplemented with cooperation because the Arabs, being little more than desert nomads, were incapable of running the complex mechanisms of administration necessary to govern the cities they had seized. They allowed Christians to remain in administration because otherwise these cities would have collapsed. Once those Christians passed their knowledge on to the Muslims, things changed rapidly. These were not mere taxes levied on people of the book, but systematic oppression which could only be escaped by apostasy. We will cover this another time.

See Peter Frankopan; Call From the East

Economy, Economia (Greek οἰκονομία, oikonomia) meaning loosely household management, is the patristic notion of allowing an exception - most often on an individual basis - to a canon or prescription of the Church for the benefit of one’s salvation. You could think of canons and penances in this regard as medical treatments, which the priest - the physician of one’s soul - divvies out the way he feels will restore one to health the quickest after a fall into sin.

It should be noted that the Apostolic Canons and Council of Chalcedon both expressly forbid clergy from holding secular offices or taking military command. The Church of Rome, then and now, verbally affirmed their acceptance of those councils.

While I certainly don’t agree with the innovations which the Papacy adopted, it’s important that we understand the very difficult position the Western Patriarch was in at the time and how it led to where it did.

Most soldiers in the thematic armies were yeoman, or small holding farmers. Each soldier in a particular theme was given a piece of land as his own in exchange for his service. This land - and military obligation - would be passed down in families. Officers were often larger landholders and got along fairly well with their Western counterparts. As a village had a particular levy of soldiers based on these land agreements, they could forgo sending men to war if it was too big a burden on production. The state allowed this in order to maintain productivity - and their tax base. To do this, they would simply pay of hiring and maintaining a number of mercenaries equal to their allotment. As time went on, more and more opted to do this. This is, in part, what enabled the empire to hire so many Western knights prior to the crusades.