The Eighth Century Renaissance: Part 1 - Roman Resurgence

The Triumph of Orthodoxy and the Macedonian Renaissance

The eighth century was a pivotal time in history. It was both a century of war and conquest, of devastation and shifting allegiances. It was also a century which marked the beginning of revitalization for the Franks, the Romans (Byzantium), and Islamic Caliphate. This series seeks to tell these stories and how they are connected. This article deals with Byzantium, or as it was known to its inhabitants and the wider world, Romania (The Roman Empire).

By the eighth century, the Eastern Roman Empire seemed on the verge of collapse. The glory days of massive public works and conquests which the empire had seen under Saint Justinian the Great had passed. After Heraclius' defeat of Sassanid Persia, Saracen armies had burst forth from Arabia. Not satisfied with seizing the whole of Persia, the Arabs swept through Syria and North Africa brushing aside what little resistance the Romans could offer. While these major defeats would spell the beginning of the end for most empires in history (the Hittites, Assyrians, Neo-Babylonians, Parthian, Seleucidan, and now Sassanid Persia), Romania would undergo a seemingly miraculous recovery and reclaim much of its former glory.

A Century of Crisis

Heraclius I, the hero of the Great Persian War, had restored the empire’s borders and began instituting reforms to put the empire on a better footing to meet future challenges - from wherever they may emerge. But while the two great powers had been warring, there had been historic amounts of rain in Arabia. This vastly expanded harvests for decades, resulting in a swollen population. This is what allowed Mohammad to build an army.

When this army burst forth from Arabia, it was met by two utterly exhausted empires. The spread of the Monophysite heresy in Syria, coupled with the large Jewish populations, had strained the relationship between them and Constantinople. More often than not, these populations collaborated with the Saracens, allowing them to conquer important cities in the Near East. But as they moved into Anatolia (by this time the heartland of Romania) they met stiffer resistance; the Saracens shifted focus to finishing off the Sassanids and taking Monophysite Egypt, before moving on to Africa.

While they were able to halt the Saracens in Anatolia, the loss of Syria and North Africa caused a crisis of confidence in Romania. The empire had lost three-quarters of its tax revenue, and trade in the Mediterranean dropped to their lowest levels in recorded history. The throne became a game of musical chairs when seven emperors came and went in twenty years (commonly called the Twenty Years’ Anarchy), and the Saracens continued to beat the Romans on land and sea. And they were about to appear before the walls of Constantinople itself, an army over 100,000 strong with a fleet so large that those who saw its approach claimed it looked like a forest had grown atop the sea itself.

Leo III and the Siege of Constantinople (718)

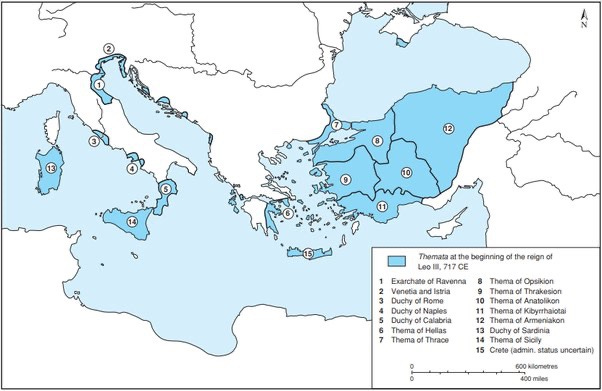

Emperor Leo III (or Leo the Isaurian), came to power in 717, ending the Twenty Years’ Anarchy. He did so by inventive means. He had been Strategos (Military governor) of the Anatolikon Theme under the emperor Justinian II and went into rebellion. Leo’s territory was in a precarious position, and historians aren’t quite sure whether he was a vassal of the Umayyads or allied with them strictly for his own gain. But Leo was notoriously crafty.

A Saracen commander, Maslama,1 crossed the Taurus mountains with a large army intent on taking Constantinople. Both Arab and Roman accounts state that their baggage train and up to 1,800 ships had stockpiled multiple years’ worth of provision, even bringing wheat to sow the next spring. The Saracens were in it to win it. Leo met with and convinced Maslama to support his bid for the throne, saying that he was wildly popular in Constantinople, and with the support of the Saracens, the citizens would let him in and proclaim him emperor. Once emperor, Leo would simply open the gates if the Caliph would make him Emir of the Romans. Maslama agreed, and aided Leo in making his way to Constantinople.

Entering the gates of Constantinople, Leo took the throne. But once there, Leo sent them a letter which basically said, “actually, JK lol, they don’t want to surrender.” In mid-August 717, the Saracen army surrounded the city. But as its fleet moved to surround the city, its notorious tides and winds (which the Arabs were unfamiliar with) caused twenty or so supply ships to stall, creating a bottleneck. Roman ships rode out of the Golden Horn and doused the ships with Greek Fire, burning up a large portion of the Saracen fleet. The Arab fleet was built and manned largely by Egyptian Christians, who now defected to the Roman side, bringing in the provisions from their ships and boosting Roman manpower.

As autumn set in, Leo had spread rumors to the Arabs that the city didn’t have enough food for winter and harsh rationing was already taking a toll; he created an impression of low morale and increasing desperation. Maslama sent a letter via an ambassador asking for Leo’s surrender. Leo’s response was legendary.

Leo said that the people were getting desperate and were willing to surrender but were afraid the Saracens would sack the city and leave. They would be more comfortable with surrender if they felt Maslama was going to stay and rule them. To convince them of this, Leo suggested Maslama send some wagons of food into the city as a show of good will and burn their supplies to signal that they would not sack the city and abandon it to starvation.

One would think that having been deceived by Leo already, Maslama would tell him to shove it… But he agreed. Maslama sent wagons of supplies into the city and burned a large portion of their food stocks before the city. One can only imagine Leo getting word of the burning mounds of supplies.2

The winter of 717/718 just so happened to be a particularly harsh winter. Without their supplies or fleet, the massive Saracen army quickly turned to eating their animals, and then their dead. Meanwhile, the Romans still had access to the bountiful waters of the Bosporus in the protected harbors of the Golden Horn; the lack of a full encirclement meant that they could bring in at least some supplies from Thrace. Roman embassies formed an alliance with the Bulgars, who attacked the starving Saracen camp, inflicting heavy casualties.

Spring of 718, two Egyptian fleets came to reinforce the Arab army. They met a similar fate as the first when the Romans opened up their siphons, showering the fleet in Greek Fire. Taking shelter on the Asian shore, they were blockaded by Roman forces, and the Arab camp continued to starve before calling off the attack in the summer of 718. What remained of the large Arab fleet sailed for Egypt and were hit by a storm; a handful of battered ships is all that returned to Egypt.

This campaign devastated the Caliphate’s navy, ending Saracen supremacy at sea, and the Romans would even launch naval raids of their own against Syria and Egypt over the next two years. The new Caliph, Umar II, halted campaigns to expand the Caliphate and even considered withdrawing from Spain and Central Asia entirely. To compensate for the severe loss of prestige they had faced, the Saracens launched a brutal campaign of forced conversions against Christians in their realm, many chose martyrdom.

For the empire, and all of Christendom, this was an unparalleled victory. It proved that the Saracens were not invincible and prevented them from expanding into the Balkans and Europe for the next seven centuries. The people of Constantinople sang hymns, led processions around the walls and through the streets of the city to thank God and His most pure and blessed mother for delivering them from destruction.

But they were not out of the woods just yet.

The Age of Iconoclasm

While Constantinople had been spared, the empire was in rough shape. Its countryside devastated by war, plague, and civil war; Romans could only wonder what they had done to draw the wrath of God.

Leo was known as the Isaurian, or alternatively, the Syrian, and may have spoken Arabic as a first language. Leo, like many from the recently seized Near Eastern provinces had been heavily influenced by anti-Christian polemics. Theophanes the Confessors (one of the prominent sources of the time) tells us Leo was “Saracen minded.” Leo, taking a cue from the Muslims, found the cause of God’s wrath in the ancient practice of Christian iconography. In 730 he issued an Imperial edict denouncing the veneration of icons and launching a war on religious imagery. What followed has become known as the age of Iconoclasm.

The iconoclastic struggle was largely a struggle between the classical Christian culture which had flourished since the time of the Apostles, and the growing influence of Eastern influences in Syria - largely caused by Islamic domination in the region and Rabbinic arguments after the Jews had cast off their own iconographic traditions. Leo’s war on Christian piety resulted in a fundamental shift in the relationship between Romania and the West.

Relations with the West

Up until now Constantinople had been indisputably recognized as the seat of the Roman Empire. Isidore of Seville proclaimed that “Constantinople is now the seat of the Roman empire,” and Pope Agatho addressed emperor Constantine IV as “Lord of all Christians,” in 680. The city of Rome was little more than a provincial town at this point and hadn’t anything even resembling an emperor in over two hundred years. Constantinople, by contrast, was the premier city of the Middle Ages.

Deprived of North Africa and the Balkans, Emperor Leo III clamped down on revenues in their remaining Western territories. He imposed a poll tax on the farmers of Sicily and Calabria, as well as the Papal lands.

A lot of imperial land in the West was in trust to the Church of Rome. This freed up imperial manpower and provided the Church with revenue to handle social affairs in Italian lands. Since the church was closely associated with the emperors in Constantinople, this was a form of soft power in which the Italian peoples not under imperial control continued to look favorably on Romania because of the aid they received from its Western Patriarch.

Pope Gregory II was not happy about the taxes and protested, refusing to pay tribute. This probably would have blown over, but Leo inflamed the situation by confiscating the papal lands in the late 720s. This significantly reduced trade and goods moving up the peninsula to Rome. Coupled with Leo’s 730 edict against the veneration of icons (and Gregory II’s response) the people of Italy turned on Constantinople and stood with the Pope in rebellion. The Exarch of Ravenna was killed, and would change hands between rebel Italy, the Lombards, and back to Romania. The churches of Sicily and southern Italy were transferred to the Patriarchate of Constantinople - and would remain a bulwark of Orthodoxy until the time of the Normans.

Gregory’s successor, Gregory III, held a council in Rome in 731 rejecting Leo’s iconoclasm and upholding the veneration of icons. While Pope St. Martin had upheld Orthodoxy against the Monothelite heresy, he did so as a bishop of the empire and was silenced by Roman arms. Gregory III was the first pope to truly act as an agent independent of Romania.

The city’s militia was now loyal to Pope Gregory above anything else, and even imperial families in Italy were becoming increasingly loyal to the Pope, not the empire. These were the first signs of what was to come, and although he would restore Rome and Ravenna to the empire (nominally at least, Rome was now essentially an autonomous papal state) in 739, Gregory would become the mechanism by which emerged a split between east and west, which remains to this day.

Two years later, in 741, Leo III’s son Constantine V “Copronymus” (ie., “the dung-named) came to power. While the controversy erupted under Leo, persecution began in earnest under Constantine. He forced Orthodox bishops and clergy into exile, replacing them with bishops who wouldn’t resist his Judaizing tendencies. He arrested, imprisoned, and tortured monastics, and churches were ransacked across the empire.

Constantine V was a competent commander, and under him the military reforms which Heraclius had set in motion would come into their own. These highly mobile field armies scored a number of small victories in the east which were crucial to rebuilding Roman confidence. This won him the favor of the army, who supported his iconoclastic policies and helped him carry out his persecution of the populous - especially the monastics.

The New Roman Army

Heraclius had begun the process of reforming the structure of the Roman armies and territories in the East. This system, known as the Theme system, would reach its peak in the tenth century. The core of the army was the Tagmata, elite professional soldiers organized into mobile field armies. In addition to this were the Thematic armies. These served a function similar in many ways to the earlier Limitanei - though they do not appear to be connected.

The themes replaced the older provincial, or diocesan system which had prevailed in earlier centuries. Themes were militarized provinces in which the old model army had largely been settled and the soldiers given land in exchange for service - the government was unable to pay salaries at this time due to the significant drop in revenue. These men became citizen-soldiers, part time farmers, part time soldiers. This military obligation was passed on from generation to generation, and soldiers drilled regularly. Population transfers with land grants and a draft system would later be implemented as well to increase the pool of available soldiers.

When Arab raids came, thematic forces would organize a defense. For larger incursions, they would often wait for the tagmata to arrive, screening the enemy to gather intelligence and harass them along the way. Each theme had a military governor, a Strategos (sometimes Stratelates, plu. Strategoi) who played the role of both commander and governor. These men were appointed by the emperor and paid by the central government, wielding tremendous power for most of the period.

Thematic forces proved highly effective both in guerilla/defensive tactics, as well as in offensive operations. These forces became powerful enough to wage wars all on their own but were often used to beef up the professional forces of the Tagmata.3

The Roman Army had become much more of a combined arms force than during the days of the legions. They were now a mix of infantry, cavalry, and specialty troops. This change in composition was an evolution which had been taking place since the crisis of the third century and was necessary to battle the cavalry heavy armies of the east. But it was in the realm of tactics and formations which really set the armies of the Tagmata and Themata apart from their contemporaries.

The army adopted an innovative square formation which in some ways foreshadowed the Swiss Pike and Shot Square. This was a hollow square which served as a sort of mobile base camp both on the march and in battle.

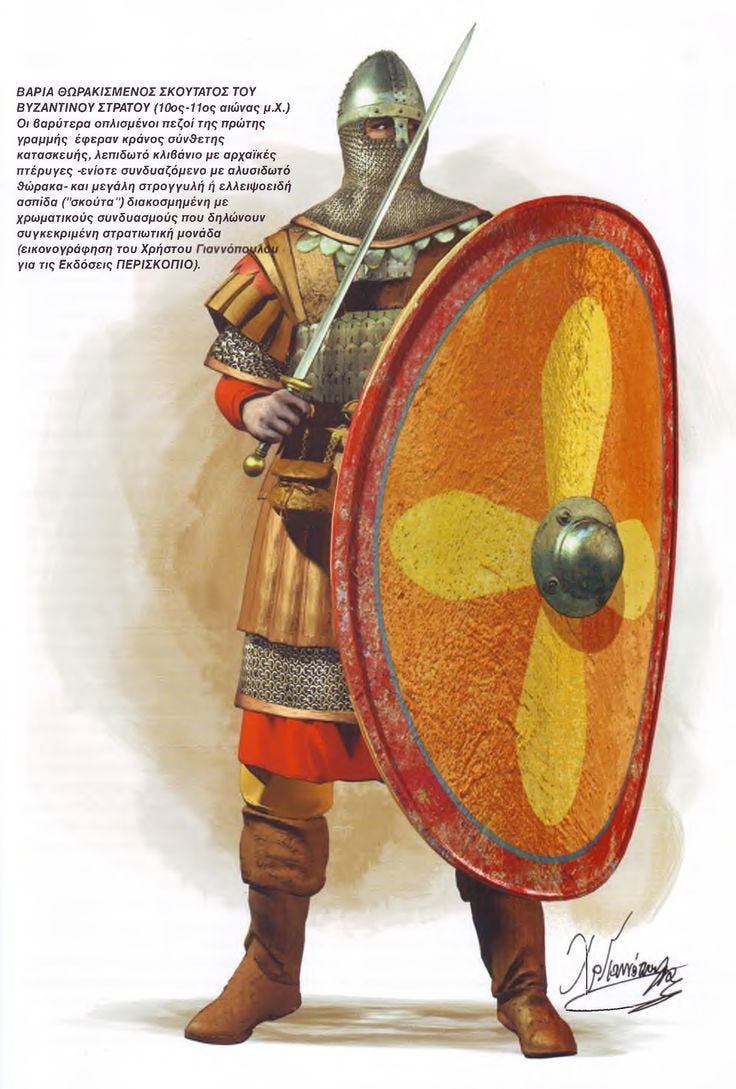

The outer shell was made of heavy infantry known as Hoplites (skutatoi). Hoplites were highly trained, well-disciplined, and the backbone of the army’s survivability. They were heavily armored from head to toe, in addition to wielding oversized shields. While armament would change over the centuries and from unit to unit, most hoplites carried spears/pikes, a bow, and sword. Their main task was to firmly plant their shields in a locked shield wall and brace for impact from a cavalry charge.

Behind the Hoplites, and working in tandem with them, were the Menavlatoi. Also well armored, menavlatoi were armed with a particularly long, thick pike. These pikes would be planted firmly in the ground, stick out in front of the hoplite shield wall, forming a sort of human palisade.

Behind these outer ranks would be found lighter infantry, skirmishers, and later grenadiers armed with grenades and potentially flamethrowers; crucial supplies and sensitive personnel were also kept in the center. The square formation’s shape denied the enemy the ability to outflank the Romans and allowed troops to be transferred from side to side as needed, or easily rotated from the front to relative safety to rest, rewater, and seek medical attention.

Another benefit of this formation was that if the cavalry needed to fall back, the infantry ranks could open to allow the mounted forces to enter the safety of the square. It was a fantastic defensive formation, its simplicity and the superb training of the troops allowed it to maintain cohesion in the confusion of battle, even when surrounded by mounted steppe archers. While the infantry covered the defensive needs of Roman forces, its offensive capabilities lay primarily in its mounted forces.

Sassanid heavy cavalry, called Cataphracts, and horse archers (typically drawn from the Persians steppe nomad allies) had devastated the legions nearly every time they went East. The Romans adopted and improved upon the Sassanid model. So important were the empire’s mounted forces, that the emperors maintained large horse farms in Cappadocia for the purpose of breeding and training mounts for imperial cavalry.

The Romans primarily employed two types of cavalry forces: medium mounted archers (sometimes known as tasinarioi), and heavily armored Cataphracts (Greek: Kataphraktoi), who served as the shock troops of the Roman army and were its most precious asset.4

Horse archers had to be not only excellent archers, but first-class horsemen; much to their dismay, the Romans found that even after five years of hard training, their horse archers were easily outclassed by steppe riders. To excel at the job, one had to grow up in the saddle. For this reason, the army often recruited from rougher areas of the empire and nomadic allies living in or near the empire whose cultures emphasized these traits, and this allowed the Romans to produce elite formations of mounted archers.

The mounted archers’ primary function was to weaken the enemy front by making repeated passes and falling back - often to soften them up for the Cataphracts to break through. They were also instrumental in a rout, as their lightly armored mounts could move over large distances when necessary. Mounted archers were excellent in scouting and screening roles; they had mastered the art of feigned retreat, drawing enemy forces into an ambush - which the Romans came to specialize in.

The cream of the Roman army, however, were the Kataphraktoi.

Cataphracts, like the heavy infantry, were heavily armored - as were their horses. They carried an assortment of weapons including spears/lances, bow, sword, dagger, and the mace. Tenth century accounts note a real preference for the mace (a club with a heavy metal end, usually equipped with spikes to pierce the most well armored skulls) in hairy situations, and this was a point which Roman Kataphraktoi and Western knights bonded over during the crusading period. Similar to Western knights, the Cataphracts main role was to break through the enemy’s lines to force a route, at which point they could kill as many enemy fighters as possible.5

The Roman’s still carried with them a number of allied forces on campaign when necessary. This provided the army with various types of light and medium cavalry (or heavy in the case of Western knights, crusader or mercenary), infantry and archers. Roman siege craft could also be quite advanced when they had the resources to carry out such operations.

There was also a large number of specializations within the Roman army, allowing it to quickly adapt to situations are they arose. This was crucial in the environment they were operating in, as no one was coming to help them. Roman forces avoided a direct confrontation whenever possible, preferring to ambush/hit and run. They simply didn’t have the ability to raise an equally effective army to replace an army lost in battle. Modern Roman forces were highly trained, well disciplined, and expensive. But when they attacked, they tried to do so in a manner which ensured victory - brains were preferred over blind courage. For this, they were mocked by their Western contemporaries whose militarized feudal culture exalted those who died in an act of blind courage - which cost the Crusaders dearly a number of times.

Stumbling Forward

The tide began to turn under Empress Irene, an Athenian born woman renowned for her beauty and piety who married Constantine V’s son Leo IV. Their son, Constantine VI, ruled for ten years with his mother as regent. It was during this time, in 787, the Seventh Ecumenical Council was held in Nicea, restoring the icons and Orthodox Faith, as well as the communion between the Eastern and Western Churches.

Interest enough, Irene also sent Konstaes the Sakellarios (a high court official) to the court of Charlemagne, King of the Franks, to arrange a marriage between his daughter Rotrude (Erythro in Greek sources) and her son Constantine. An agreement was reached and Konstaes remained to teach Rotrude the “ways of the Romans.”

The Franks had won a great deal of prestige for halting the Muslim advance at the Battle of Tours in 732. But the emperor in Constantinople was, as Pope Agatho said, the emperor of all Christians. In the eyes of Romania, all the Western lands were still theirs by divine right. Local kings ruled there only by circumstance - and often they sent for the Roman emperor's blessing to rule upon ascending the throne. In Irene’s mind marrying the young emperor to the daughter of the Frankish King could bring most of the Western territories back under Constantinopolitan rule.

This was not to be. Irene sabotaged the marriage and tried to force Constantine to marry a well-born Anatolian woman. He resisted and proclaimed his loyalty to the oath he made to Rotrude. Irene eventually killed her son, claiming the throne for herself as the first empress of Rome. Irene’s great sin would solidify the changing perspectives of the empire among Christians in the West. Constantine VI was the last emperor to be acclaimed by the Western kingdoms as the universal emperor of the Roman Empire.

Pope Leo III refused to recognize Irene’s rule, saying that a woman couldn’t rule Christendom. It’s somewhat ironic then that he petitioned Irene for help when his enemies came to oust him from the Papal throne. Shortly after firing off that plea for help, he fled to the court of Charlemagne. With the help of the Franks, Leo was reinstalled on the Papal throne. In exchange, he crowned Charles the “Emperor of the West,” in 800 AD.

“Charlemagne was a chieftain of the Franks… He gave [Pope Leo] his powerful hand as an ally, and again established him in the city and on his throne. Afterwards, in exchange Leo proclaimed Charlemagne emperor of the Old Rome and placed the crown on him in accordance with the laws of the Romans. However, he also incorporated the laws of the Jews and anointed him with oil from his head to his feet, with what reason or purpose I do not know. Thus, the former bond between the cities was broken. The sword fell between mother and daughter, severing and dividing with the sword of wrath a good-looking maiden, the New Rome, from the wrinkled, ancient, senile Rome.” - Chronicle of Constantine Manasses, pg. 179-180; Liverpool University Press, Liverpool 2018)

Irene protested the crowning of Charlemagne, but there was little she could do. She herself would be overthrown two years after the crowning of Charlemagne by a senator named Nikephoros. She was forced into a convent to mourn her great sin, and Iconoclasm would soon return in violent force.

Nikephoros I

Nikephoros would do a lot to solidify the reforms happening in the army. During his tenure, the Balkan territories the empire still held were fortified through a population shift from Anatolia. These settlers were given land - and with it a military obligation. This helped to quickly establish the thematic system in the Balkans, which, until this time had still been under the old prefecture system - due in part to their large populations of Slavs who weren’t overly loyal to the empire. The ranks of the thematic armies were bolstered by a more in-depth registration process for smallholders. While many weren’t thrilled by this, it helped to bulk up the armies so necessary for the survival of Romania.

They could opt instead to pay a fee covering the cost for the government to hire a professional soldier. The government was happy to oblige as, at scale, this could allow them to purchase a professional mercenary force for a campaign. Additionally, each theme established a core unit of well-trained, full-time soldiers. These units could be requisitioned from across the empire to join the emperor and tagmata on campaign, as well as filling a number of other necessary roles.

The battle of Versinikia

In July of 811, Nikephoros invaded the land of the Bulgars. His army contained the tagmata and units from virtually every theme, drawing especially heavy from those on the European side of the Bosphorus (Anthony Kaldellis estimates the army at around 20,000. This was large for the time).

Nikophoros managed to defeat the Bulgars twice before moving on to sack the capital and burn the palace of the Bulgar Khan, Krum. Theophanes tells us that with his capital sacked, Krum asked only that the Romans take what they gained from the sack of the city and return home in peace. But the Romans turned west and continued to pillage, infuriating Krum, who then had the mountain passes sealed. The Romans were overconfident, and discipline began to break down. While moving through the Haimos foothills, scouts reported that the passes ahead were blocked. Nikephoros, believing the Bulgars defeated, pitched camp in the valley - what followed was the worst military disaster Rome had faced in centuries.

The army awoke at dawn to the sound of horns, and of steel piercing unarmored flesh. Panic ensued, the Bulgars were everywhere, and it was quickly every man for himself. The army was slaughtered nearly to a man.

It is said that Krum cut off Nikephoros’ head and, “laid bare the bone of the skull and plated it all around with silver and ordered the Bulgarian leaders to drink from it (Chronicle of the Logothete, 121.10; Liverpool University Press, Liverpool 2019).”

With the armies north of the Bosphorus shattered in a single night, Krum’s Bulgars became the bane of Roman existence. The Bulgars’ star was rising, and with the thematic armies occupied with defense of the east Krum’s forces raided the remaining Roman territory in the Balkans at will and laying siege to Constantinople itself.

The Triumph of Orthodoxy

But just as it seemed the walls were closing in, Krum died, and the pious Empress Theodora and her son Michael III came to reign. On the first Sunday of Holy Lent, 843 AD, Theodora and the Patriarch Methodios reaffirmed their Orthodoxy, giving peace to the Church and ending the age of iconoclasm for good. This event has been immortalized in the Orthodox Church as the Triumph of Orthodoxy, celebrated on the first Sunday of Lent every year.

This was the turning point of Roman fortunes, the fruit of Irene’s pious deeds early in her regency. The worst was behind them, and the reign of Michael III would launch the empire to new heights.

Conversion of the Slavs

The Patriarch of Constantinople, St. Photios the Great, had received a message from Michael III that the king of Moravia, Rastislav, had asked for men to be sent who were learned in the Christian faith and understood the Slavonic language. He sent a former pupil of his, Cyril, and his brother Methodius. Cyril had previously studied under St. Photios and Leon the Philosopher (sometimes called “the Mathematician,” Leon was the former bishop of Thessalonika), and had faithfully served both God and country as part of an embassy to the Khazar Khaganate shortly after the Rus’ first appeared on the shores of Constantinople in 800 AD. Both brothers were brilliant, Godly men; but Cyril was a particularly astute philologist and champion of the Orthodox faith against Islamic and Jewish polemicists.

The brothers traveled to Moravia and Cyril developed an alphabet for the Slavonic language known as Glagolitic - this would later be reworked and named Cyrillic in his honor. Frankish missionaries arrived and caused a scandal (as they were wont to do) claiming that translations and liturgy could only be done in Latin, Greek or Hebrew. The brothers reminded them that the Armenians, Syrians, Goths, Georgians, Copts, and others all worshiped in their own languages. The Pope silenced the Frankish missionaries, siding with the brothers.

While things would change and the Franks would succeed in pushing out Methodius after the death of Cyril, the work they did allowed for the evangelization of Slavs - who then brought Orthodoxy to America. They are rightfully known to history as Saints Cyril and Methodius, Apostles to the Slavs.

After the Caliphal invasion of 838, the Caliphate began to disintegrate, devolving for a time into smaller fiefdoms. In September of 843 the Muslim Emir of Melitine, Umar al-Aqta (Amer in Greek sources), launched a campaign against Romania. He was met by Patrones, the Stratelates of the East (commanding general of the eastern armies), and Nasar of the Boukellarioi (a sort of imperial guard), at the battle of Lalakaon river. They managed to rout Umar’s forces, chasing him down and cutting off his head. This established near total peace in the east for the time being - the first in centuries.

The Chronicles tell us that one year later (864), Michael’s uncle, Caesar6 Bardas, led an army against the Bulgars. The Bulgars approached and informed Bardas of their terms: that their tsar, Boris, and all his people would be baptized into the Holy Orthodox Church. Boris and the boyars (sounds like a blues band) went to Constantinople and were baptized. Boris took the name Michael after his Godfather, the emperor Michael III. The Bulgarians entered into a fraternal alliance with Romania.

In a very short time, the Moravians and Bulgars had been baptized and made friends and the Arabs had been checked in the east. The alliance with the Khazars7 had been renewed to check the expansion of the Rus’ - who now agreed to a trade agreement with Romania.8 The empire, having emerged from the darkness of heresy and returning to the light of Holy Orthodoxy, began to see the sweet harvest of the seeds planted by Irene and the Iconophiles during the second half of the eighth century.

Cultural Revival

The end of iconoclasm ushered in an age of unprecedented learning. While some have called the eighth (along with the seventh) the Byzantine Dark Ages, this is not exactly the case. While it is true that the universities closed and there was a sharp drop in chronicles from the time, there are few things to consider. The monasteries (always centers of learning) remained open, even if severely persecuted; there is no indication that the Patriarchal Academy ever closed. Histories and works of art were often paid for by emperors, and these didn’t seem to hang around long before being replaced - or were out on campaign.

With iconoclastic figures in power both in the palace and patriarchate, there would have been a marked decrease in artwork (I mean, it's literally the age of the “image breakers”), and histories being written by the Orthodox would have been destroyed when found - just as many of the iconoclastic histories were destroyed after the Triumph of Orthodoxy. There was certainly a downturn in learning, but the connection between Romania and Antiquity was never severed. This is made clear by the period of history we are currently discussing - as we are about to see clearly.

Caesar Bardas organized a university at the Magnaura palace which became an important hub of secular learning. Under the guidance of Leon the Philosopher full-time scholars gave lectures in rhetoric, philosophy, engineering and the sciences. Prominent philosophers, theologians, and rhetoricians from across the empire came to lecture and debate ideas with their peers - and before the emperor. All of this was paid for by the royal family. It is from this period that we derive our oldest manuscripts of Plato and the Neoplatonists; there was a flourishing of Aristotelian rhetoric and commentaries, as well as the composition of Encyclopedia on every subject.

A number of impressive inventions appeared as well.

The mountain top fire relay of Lord of the Rings is itself inspired by an invention of Leon the Philosopher, the optical telegraph. This stretch of beacons connected the Anatolian frontier to the palace and was able to relay a message from end to end in one hour. Synchronized clocks on each end meant that the time a message was sent/received could carry a specific message. Evidence of this system has even been found in southern Italy.

Many are familiar with Greek Fire, a form of waterproof, flammable gelatin fired from a siphon to ignite ships. But the Romans also made land-portable versions, both to mount on city walls and transport with the army. While we have yet to find one intact, chronicles from the era claim the Romans had invented a man-portable version. Additionally, we have found examples of incendiary and explosive grenades filled with Greek Fire.

There’s also the case of Damascus steel, an incredibly durable steel with a beautiful pattern on account of the manner of its construction - which modern metallurgists have been unable to replicate. That we cannot replicate Greek Fire and Damascus steel is a testament to the ingenuity of Roman inventors and the premium they placed on state secrets.

Higher learning wasn’t restricted to the palace either - or even just Constantinople and Thessalonika. For the first time since the days of Justinian, it spread back into the themes. In many cases this was focused on the large monasteries - as was the case with the Studion monastery in Constantinople. Monastics in this time were, in addition to being renowned ascetics, the caretakers of the Roman Orthodox heritage. This was aided by the growing network of landed magnates, who donated large sums to the charitable and cultural work of the monasteries. Monasteries opened orphanages and schools to aid in the education of the rural population and the strengthening of Roman Orthodox piety and culture. It is believed that the empire maintained an average literacy rate of thirty percent even up to the time of the Crusades, which would put it on par with the golden ages of China and the Islamic world.

There was also a flourishing of art and architecture. In the wake of the iconoclastic era, churches and monasteries across the empire commissioned new works.

The monastery of Hosios Loukas (Saint Luke the Apostle) on Mt. Helicon is a treasure trove of Macedonian era marble work, mosaics, and iconography. While returning in many ways to the classical styles of antiquity, we also begin to see a spark of naturalism in some works which foreshadow the perspective and emotion of later Christian art.

In Constantinople itself, the Hagia Sophia received numerous new works whose beauty transcends time and culture. Unfortunately, many of these treasures of Christendom have been lost to time and conquest. From the Fourth Crusade to the Ottoman conquest and centuries of Muslim rule, some of the greatest treasures of Constantinople have been lost. In the case of Hagia Sophia itself, most of the loss is from botched preservation attempts; to the credit of the Ottomans, the Sultans forbade the destruction of Hagia Sophia’s iconography.

Some of the most impressive examples of Roman mosaics, iconography, and architecture all come from this era. There are many examples of elaborate gifts sent West from the Constantinopolitan courts, such as the Paris Psalter, the crown jewels of Hungary, the Harbaville and Borradaile triptychs.

This artistic renewal went beyond the borders of Romania in more ways than personal gifts. Embassies visiting Constantinople returned with gifts and first-hand accounts of the immense wealth and beauty of the empire, and this served as a key trigger for the Ottonian renaissance in the Holy Roman Empire. St. Mark’s Basilica in Venice was built on the model of the Church of the Holy Apostles in Constantinople, and the mosaics are in the style of the Macedonian renaissance. Imitation is the greatest form of flattery after all.

Much of the historical chronicles of the time paint Michael III as the drunkard. These were written during the Macedonian years; all things considered these narratives largely serve to justify his murder. And while it’s clear he was certainly not a model of how to live a pious life, he was a good ruler overall.

As George Ostrogorsky notes, Michael was impressionable, and easily swayed by the wills of those around him. His two caesars, Bardas and Basil the Macedonian, were instrumental in the sharp incline the empire was now on. This good statesmanship allowed for the great cultural revival which was underway, resulting in generations of brilliant men inside both the Church and State. And they were desperately needed - Divine Providence was at work.

The Macedonian Dynasty

Basil I was raised in Adrianople by peasant parents. Finding himself working in the imperial stables in Constantinople, a drunk Michael III befriended him. He managed to work this friendship all the way to the position of co-emperor. This says a great deal about social mobility in medieval Roman society. Scholars since the Enlightenment have attempted to paint a picture of a harsh theocratic dictatorship in which detached elites taxed destitute serfs into the ground.

But the scholarship of the last century has gone a long way in reversing these false narratives. Afterall, the greatest emperor in East Roman history (and one of the greatest in all Roman history) was St. Justinian the Great, a Balkan peasant turned emperor. Over a dozen emperors got their start as peasants, and more as soldiers. Basil was simply the latest peasant to reach the throne and, like Justinian, would do a great job. Basil and his son Leo (VI) the Wise would even be compared in the popular imagination to David and Solomon, having risen from shepherds to royal stock.

Under Basil, a new aristocracy began to emerge. The senatorial class had survived through the sixth century, but largely died during the seventh along with the city councils from which they were usually drawn. But the emerging aristocracy was not yet what it would become by the late tenth century, though they were often large landowners.

The population of Constantinople was growing as well. Much of this was due to internal migration, but trade was increasing as well since the Romans had largely checked the Caliphate at sea. A strong navy was crucial for Romania to keep its territories connected. Aside from the Peloponnese and Anatolian coast, they maintained a number of settlements in southern Italy and Dalmatia. Led by Niketas Ooryphas, the Roman fleet liberated town after town along the Dalmatian coast.

After the so-called “emperor of the West” Louis III was exiled by his own people in Benevento, the imperial fleet was able to take Otranto, Bari, and Taranto, in time clearing both the Lombards and Saracens from the region. Now having control of Apulia and Calabria (swollen with Greek speakers since the fall of Sicily to the Saracens), the Romans regained their position in Italy. But Basil’s real successes were in the East.

After the defeat of the Emir of Melitine, Basil turned his attention to the Emir’s heretical Paulician allies, based in the fort of Tephrike (modern Dvrigi) in eastern Anatolia. Basil’s son in law Christophoros, served as Domestikos of the Scholai (commander in chief of the army) and was tasked with the destruction of the Paulicians. Leading two thematic armies, the Armeniakon and Charsianon, Christophoros stalked and routed the Paulicians, killing their leader. Basil used his head for target practice - as one does. While the Paulician leaders were heretics, much of the population were Orthodox, and the territory was easily integrated into the empire. From here the armies moved south and were able to dislodge the Saracens from the forts lining the Taurus mountains; this provided a much stronger defensive position while also severing a primary invasion route for Arab armies.

For the Romans, Armenians, and Arabs along the frontier, it was clear that Romania was again a major player in the Near East.

A fitting detail comes down to us to sum up the reign of a man revered by his people as a new King David. While they had a falling out late in Basil’s life, Basil left his son a book of instructions, a sort of moral poetry similar to the Book of Proverbs. This text, the Hortatory Chapters for Leo, was penned by St. Photios, and expressed Basil’s wish that his son would emulate Solomon in all he did - minus the concubines and idolatry, obviously. That Leo came to be known as Leo the Wise, attests to the fact that in spite of their struggles, Leo did his best to honor his father’s wishes.

With St. Photios as a lifelong tutor and spiritual father, Leo became an accomplished legal scholar, releasing revised editions of the Justinianic law code. He had an encyclopedic knowledge of Scripture, the Church Fathers, and the Greek and Roman classics and even gave homilies under the guidance of Photios. Leo and his son Constantine VII would in many ways be the crown jewels of the cultural revival of Romania.

Leo VI inherited the throne in 886. It had been a hundred years since the Seventh Ecumenical Council, and Leo now stood over an empire stronger than it had been at any time since the rise of the Saracens. At its lowest, the Romans hardly held onto the Thracian approaches to the Bosphorus, Thessalonika, and Athens. By 900, they controlled modern day Greece, parts of Albania up with settlements up the Adriatic coast. They expanded and concentrated their positions in southern Italy and their ships again patrolled the Tyrrhenian Sea. They secured land and more favorable borders in the East, showing the Saracens that they could still pack a punch.

Economic Recovery

Roman dominance on land led to Saracen raids along the coastline. Leo’s regime was able to impose a small increase in taxes along the coastline to supplement the increased defense spending needed for the Navy to effectively tackle this problem. It didn’t take long for the raids to cease, ushering in more than a century without recorded raids in Anatolia.

The essential end of Saracen raids meant that generations of farmers were able to invest and reinvest into their farms and estates, to diversify their incomes, and have more children. It also meant that the government didn’t need to send aid nor remit the taxes of eastern themes subjected to large scale raids. More lands, being more productive, meant more revenues and this was the heart of the Roman revival.

The Roman silk industry (the result of Justinianic spies learning the trade in the far east and smuggling out silkworms) made an impressive comeback, and the majority of silk examples remaining from that time in Europe are Roman. Trade agreements with Azerbaijan, Bulgaria, the Rus’ increased imperial profits while building goodwill with regional players. Roman goods from silks, silvers, and ceramics were in high demand in the east too, and merchants from east and west mingled in the markets and ports of Constantinople. But merchants did not make up the elites of Constantinople, nor were they well regarded in Romania. The elites came from the large estates forming in Anatolia.

Land was still the basis of the economy in Romania, and the majority of Roman citizens were free smallholders. Lots of land had been abandoned, or left fallow during the seventh and early eighth century, and Romans had the right to claim this land if they were willing and able to work it and pay its tax burden. In this way, extended families could pick up a great deal of land in a few generations.

Smallholders weighed down with debts often sold their land to these local families either in exchange for the payment of debts and a ticket to the city, or they would stay on the land to live and work for the local magnate family. The Venetian slave trade further allowed the magnates to work their land or diversify their income by forming workshops. Often, a community would pool their resources to work the vacant fallow land to bring in extra cash, to cover the lands tax burden (which was assessed on a communal basis), or to cover their military obligations.

Macedonian Renaissance?

This was only the beginning of what has come to be known as the Macedonian Renaissance.

While the Macedonians get much of the credit, it was the hard-fought battles (both at home and abroad) and reforms of the mid-eighth to mid-ninth centuries which saved Romania and allowed it to flourish under the Macedonians. From Irene to Theodora the bleeding had been stopped and the empire was restored to health. Basil I certainly had a hand in many of these reforms - as we noted - and the improvement of relations with Romania’s neighbors, and while I am by no means writing off the successes of Basil and his successors, the grunt work which allowed them to take place, took place prior to their ascent.

The systems of state which Rome inherited from Antiquity largely evaporated as a result of the plagues and wars which rocked it during the mid-sixth to eighth century. These institutions were reformed or replaced resulting in a more agile regime and less cumbersome military infrastructure.

The iconoclastic controversy was in many ways a struggle between Rome’s Christian Antique worldview and the Persian/Arab influences rising in their former territories. The victory of the former, and the loss of the lands in which the latter held sway, resulted in a much more homogenous Roman civilization - more homogenous than any time in Roman history.

This is an important point to make. While the eighth century was a time in which the influence and cultures of the Frankish and Abbasid empires grew rapidly, the groups they conquered in expanding had no reason to buy into the system but force. When things got rough and the “emperor” or caliph could no longer beat these regions into submission, those regions no longer had cause to remain on board with the project. As a result, the Frankish and Abbasid empires fell apart.

This lined up perfectly with Rome’s stabilization and allowed them to grow once more. Divine Providence was clearly at work. The Frankish Empire and the West, so close to greatness, began to adopt heresies and soon declined.

Conclusion

While the Romans entered into the eighth century broken, bloody, and spouting blasphemy, they emerged at the end of the century revitalized and reaffirming their allegiance to Holy Orthodoxy and one another. Reform didn’t happen overnight, but when it did, a more lean and agile state emerged ready to reassert itself on the world stage. Clearly, God’s favor had been restored, and His light was beginning to shine upon the empire in a particularly brilliant way.

Restored to Orthodoxy, Romania underwent a remarkable period of growth and would rightfully regain its title as the Roman Empire. Over the next few hundred years, the empire would expand its Balkan territory back to the Danube River, and well into Syria and the Caucuses in the East. The Roman army would once again gain a reputation as the most professional fighting force on earth. It was the hegemon of Europe and the Near East, and a center of learning and culture. It built a commonwealth of Orthodox Nations which stretched from Anatolia through the Balkans and Caucasus to the Arctic frontier.

This can all be traced to the eighth century Iconomachy and the Triumph of Orthodoxy. All of this, centered upon one Christian city, with its relics and holy sites, its gold encrusted domes, renowned around the world for its greatness: Constantinople, a city known around the world simply as, “the City.”

Stay tuned for parts two and three, where we will deal with the Carolingian and Abbasid Renaissance(s) respectively.

Primary Sources:

Chronicle of Theophanes

The Chronicle of the Logothete

The Chronicle of Constantine Manasses

Leo the Deacon, the History

Constantine VI Porphyrogenitus, De Thematibus

Anna Komnenos, the Alexiad

Secondary/Modern Sources & Scholarship:

Anthony Kaldellis, The New Roman Empire

Geroge Ostrogorsky, History of the Byzantine State

Charles Oman, The Byzantine Empire

Charles River Editors, The Byzantine Army

Sowing the Dragons Teeth (tenth century Byzantine military treatises with commentary)

Robin Pierson, History of Byzantium Podcast - great way to easily learn the narrative and interesting facts about life in Romania.

NOTE: The modern theory of history takes many of the mistakes of modern secular science and applies them to historical study. The overwhelming majority of historical study is done from a modern scientific perspective, which robs us of an organic understanding of history, an understanding in continuity with the people being discussed. We end up missing a lot of important details, as I have learned in studying the various primary sources compared to modern accounts.

We must approach modern scholarship with discernment and understand that their analyses are not gospel - even if tremendously helpful. This is the case with all modern Byzantine scholars just as it was those of the Enlightenment. But this is especially true in the case of Anthony Kaldellis (whose New Roman Empire I will be reviewing soon). Professor Kaldellis does a great job in deconstructing certain prevailing narratives and building what I believe is a more accurate view of Romania - especially in regards to the mechanics of the economy, trade, law, etc... On the other hand, he butchers anything even remotely related to Orthodoxy and ecclesial history. He can’t really help this, but it needs to be understood when reading his works that his worldview skews his understanding. All we can do is pray that in their studies, the eyes of their hearts will be opened to Holy Orthodoxy and correct narratives.

It is my hope that, in time, I will be able to write something a little more systematic about Byzantine history and culture from an Orthodox perspective. This is a long-term goal, but not something I have the capacity for at this time since it will require a lot more study, contemplation, and perhaps a few trips to the region. Your support of this Substack does help to, one day, make that a reality.

Maslama was a half-brother of multiple Caliphs, including Suleiman, who would participate in this campaign, and was the nephew of Umar II, who would reign shortly after it.

This is the account which the Arab sources give. Roman sources focus instead on the military maneuvers of Leo’s defense. I believe this actually reinforces the veracity of the Arab accounts, as deception was highly frowned on in Romania and they would be unlikely to recount it. Western and Arab sources often speak of the crafty diplomacy of Roman emperors and agents, or as they would prefer to call it, Roman trickery/double speak.

Keep in mind that a large army at the time was 20,000-30,000. Surviving information shows that in the eighth century, there were roughly 80,000 soldiers empire wide.

When we consider the fairly poor cavalry tradition in earlier Roman armies, this transformation becomes all the more impressive.

For those unfamiliar with pre-modern warfare, the majority of combat deaths did not happen when two armies met on the field, but when one turned and fled in a disorganized panic (a route) and could be overrun by the pursuing force. Heavy cavalry’s role was to induce this scenario, as just the sight of a heavy cavalry charge was enough to force many lightly armed troops to turn and flee. The forces of the first crusade were able to win many a battle grossly outnumbered through well timed heavy cavalry charges. This the route still remains a deadly scenario in modern warfare, but with modern weaponry the majority of combat deaths are caused by artillery.

As had been the case since at least the time of Diocletian, Caesars were immediately under the emperors, often as a sort of crown prince. They would be outranked only by emperors.

The Khazars were a Turkic nomadic group that established a large khaganate between modern Ukraine and the Caspian Sea, they became a key ally in checking the northward expansion of Islam. The Khazars, oddly enough, had converted to Judaism as a way of adopting an Abrahamic faith that would not subjugate them to either their Christian neighbors, or their Islamic ones. When their empire collapsed, they spread throughout Eastern and Central Europe, and much of modern European Jewry are descended from this convert nation.

The first appearance of the Rus was in 800 when a fleet of ships arrived at constantinople after plundering the Black Sea coast. The Rus were Varangians (known in the West as Vikings) from Scandinavia who had set up a lucrative trading empire along the Dnieper and Volga rivers. They would come to rule the Slavic peoples in what is today European Russia, Belarus, Ukraine, and the Baltic states. Overtime they would adopt much of Slavic cultural norms and be baptized into Holy Orthodoxy.

Photios states that their leaders were baptized during this time, but we hear nothing else about it until the baptism of Vladimir the Great during the time of Emperor Basil II. One of the following is likely: the elites converted, but did not push it beyond that onto their subject peoples.. or, they were baptized to establish a trade alliance (as was often the case in Western Europe early on) but continued in their ways.