Two Ukraines: The Historical Divergence of Galicia-Volhynia from the Rest of The Ukraine, Part II(A)

Part II(A) | The Captivity of Little Russia; The Rise of the Third Rome; The Ostrog Circle, the Russian Revival, and the Spectre of Unia—XIV-XVI Centuries

Note: This is the second installment of a three-part series for paid subscribers on the historical development of Medieval Russia and Ukraine; It will cover three historical periods cataloguing the bifurcation of the population which led to “Great” and “Little” Russia (part one); the captivity of “Little Russia,” (this installment) the Union of Brest and rise of the Cossacks; and how the domination of Western Ukraine by Poland and Austria led to two Ukraines—which are currently fighting for the soul of the nation in the midst of the Russo-Ukrainian War, the great tragedy of our generation.

Introduction

We have spoken of the initial bifurcation of the Russian population which occurred as a result of steppe invasions and the loss of Kiev’s central authority. This resulted in much of the Western Russian lands coming under the authority of the Catholic kings of Poland and Lithuania. This domination by Catholic rulers would solidify the long-term division of the Russian peoples.

As this period of foreign domination dragged on, it would lead to the genesis of two distinct peoples. While we could define these groups in various ways, for the purpose of our study, we will define them as Ukraine-Rus and Galico-Ukrainians. The former we can describe as the historical population which maintained a continuity of faith, culture, and identity with their ancestors of the ancient Kievan state; this group was also amenable to Muscovy, or Great Russia, who they viewed as Russian Orthodox brothers.

The latter group, the Galico-Ukrainians, broke that continuity primarily through the adoption of the Catholic faith, resulting in the latinization of doctrine and praxis, and the Polonization of the nobility and Russian urban elite. This process was already beginning when we left off, but would progressively intensify in the aftermath of the Council of Florence.

To jump right into the Union of Brest would be a disservice to the immense struggle for Orthodoxy in this period; it would likewise make future developments difficult to understand. With this in mind, this will serve as “Part II(A)", covering the period between part I (and adding further context to those events) and the Union of Brest. “Part II(B)” will cover the Union of Brest, the Rise of the Cossacks, and the solidification of the Galico-Ukrainian and Ukraine-Rus’ identities.

1. Western Russia Under the Latin Yoke

1.1 Lithuania: The Other Russia

As the Kievan realm fell apart, many of the cities and principalities in what would today be central and northern Ukraine, Belarus, and the Baltic States, allied with the Lithuanian princes. The Russian princes were attracted by the Lithuanian princes' firm opposition to the Catholic crusaders and Mongols alike, their tenacity in battle, tolerance of Orthodoxy and general hands-off approach to rule. As these Russian principalities came under Lithuanian control, the demographics of the realm became decidedly Russian. This demographic superiority, combined with the cultural weight of Old Rus, led many of the Lithuanian nobles—and even a couple of the grand-princes—to convert to Orthodoxy.

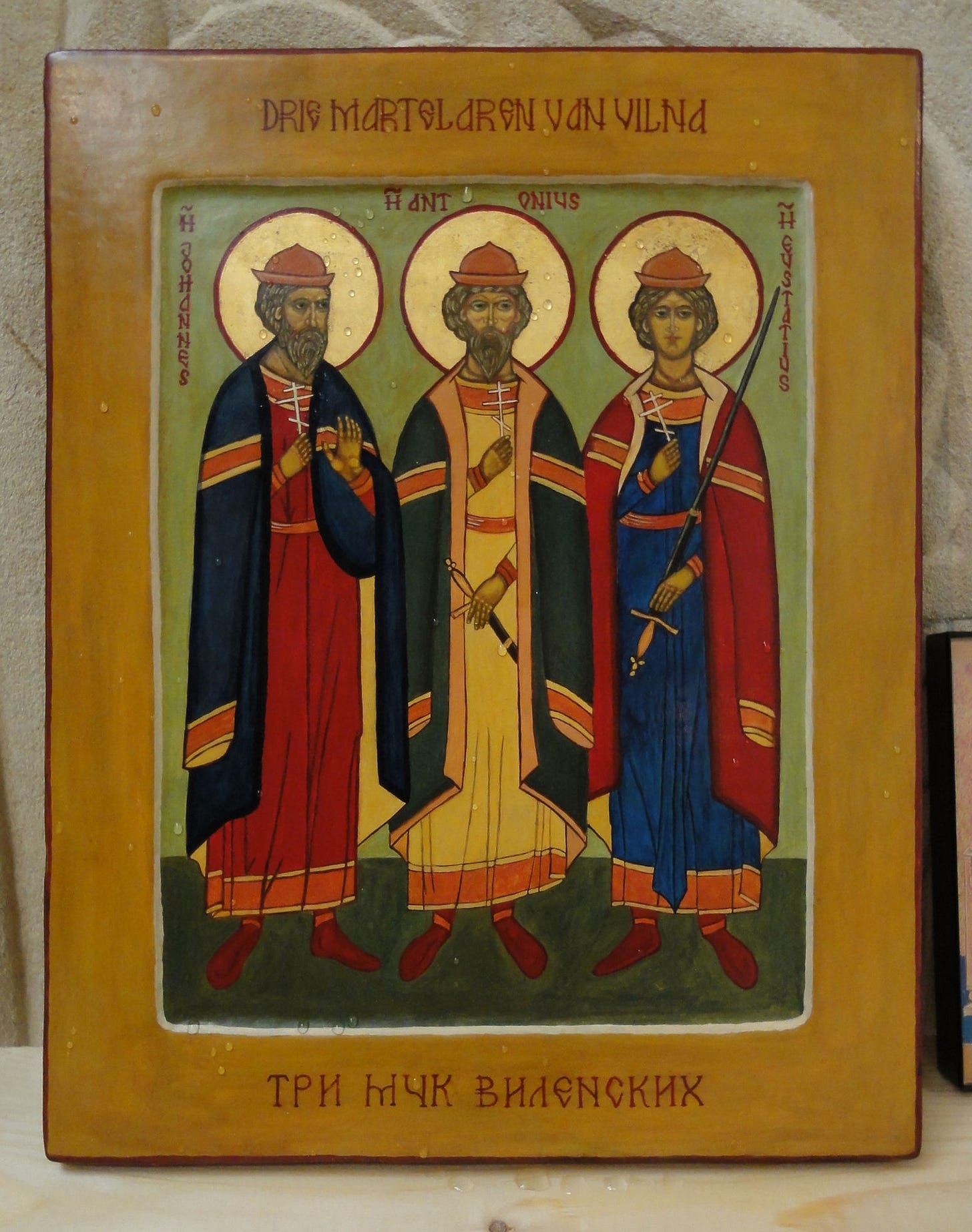

For a time, it seemed as if Lithuania was the ascendant Russian realm, with Vilna (Vilnius) and Moscow being referred to as the two Russian capitals. The Lithuanian nobility’s broad adoption of the Orthodox faith, its Slavonic liturgy and texts, meant that the nobility were largely Russianized in the early days of the Lithuanian Principality, with the court itself speaking a form of Old Belarusian.

One example of a pagan Lithuanian prince who converted to Orthodoxy was the Holy Prince Dovant (Domant) of Pskov, prince of Nalshinaisk (Nalshenk) — Timothy in baptism. He was forced to flee the infighting of the Lithuanian princes in 1265, and arrived in Pskov with 300 families.

He was moved to accept the Holy Orthodox faith, and entering the fount the chroniclers tell us “the grace of God was breathed upon him and he received many gifts of the Holy Spirit.” He was loved by the Russian people of Pskov, who elected him as their own prince only a year after his arrival.

In 1268, he fought in the Battle of Rakovor (also known as the Battle of Wesenberg). The Lithuanian Rhymed Chronicle provides us with a quote of the pious prince, delivered to his me before the decisive battle:

“Brothers, men of Pskov, who is old, that is my father, who is young, that brother. Your courage has been glorified in all countries. Before you is life and death. My brothers, let us stand up for the Holy Trinity and for the holy churches, for our fatherland.”

St. Dovont is remembered as one of the heroes who helped lead the Russian army to victory over the Danish and German armies.1 His final victory occurred in 1299 on the banks of the River Velika. He defeated a large German army and disbanded his much smaller army. But the Livonian Order had maneuvered around and launched a raid on the suburbs of Pskov, burning two monasteries and killing the monks.2

Filled with pious rage, St. Dovont refused to wait for his army to muster and set out with his revenue. Catching the Latin knights off-guard, they were forced to flee, allowing the warrior-prince and his retinue to cut down a large number of the murderous knights. Later that year, he fell asleep in the Lord and was buried in the Trinity Cathedral of Pskov.

Of course, not every noble was a St. Dovont; having incorporated large swaths of Russian land and peoples, conversion for the majority of the nobility was political more than anything. This conversion likewise never erased the different styles of rule between the Lithuanians and Russians. The Russian princes were still clinging to the administrative systems which Yaroslav the Wise had tried to set up, and for a long time the Lithuanians took a hands-off approach to the Russian principalities. But as the infighting of the Russian princes continued, their political power declined.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Where the Wasteland Ends to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.