Two Ukraines: The Historical Divergence of Galicia-Volhynia from the Rest of The Ukraine (Part I)

Part I | The Bifurcation of Kievan Russia in the XI-XIV Centuries

Note: This is the first installment of a three-part series for paid subscribers on the historical development of Medieval Russia; It will cover three historical periods cataloguing the bifurcation of the population which led to “Great” and “Little” Russia (the current installment); the captivity of “Little Russia,” the Union of Brest and rise of the Cossacks; and how the domination of Western Ukraine by Poland and Austria led to two Ukraines - which are currently fighting for the soul of Ukraine in the midst of the Russo-Ukrainian War.

It’s an unfortunate reality that most Americans are disinterested in history, especially the period between the fall of the Western Roman Empire and Second World War. While they certainly understand events of the eighteenth century onward to bear some relevance, these are largely seen as little more than a prelude to the American Century - the apex of history. As a result, they struggle to see the Russo-Ukrainian War and the internal strife in the Ukraine outside of the frame of the Cold War and the Holodomor - an event they’ve only just become even vaguely familiar with.

Recently, I wrote an article on Western Ukraine, and Lviv in particular, being a center of Banderite/Neo-Nazi activity. To understand how this came to be, and what Lviv and the wider region of Galicia mean to Ukrainian Nationalists, we need to understand the historical processes which led to Western Ukraine’s unique identity in contradistinction to the broader Ukrainian ethnos.

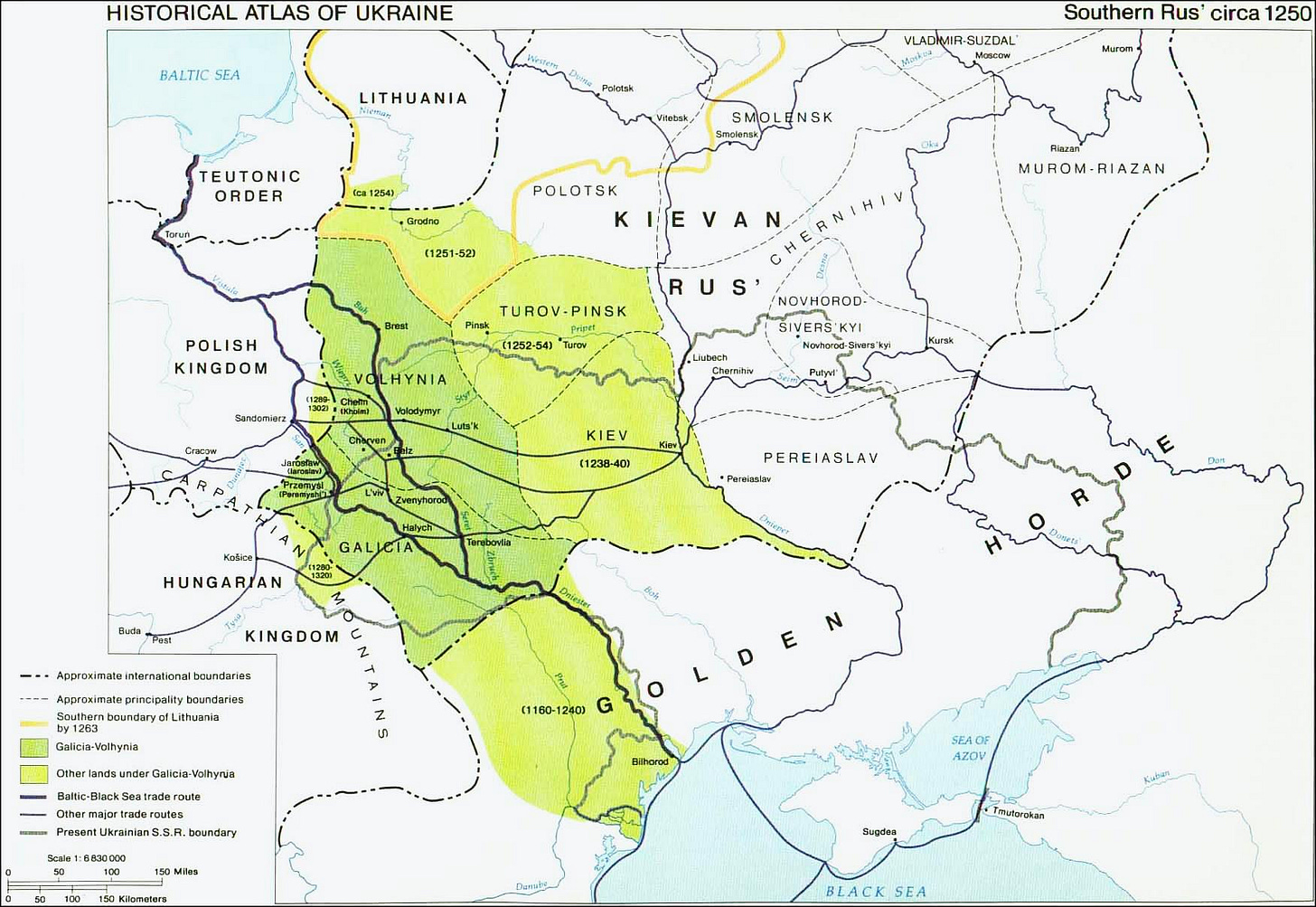

Our story really begins with the Mongol invasions, when an already fracturing Kievan Rus was finally smashed into pieces. From this time on much of Western Rus (what today makes up parts of Belarus and much of western and central Ukraine) became dominated by the Catholic powers of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth and Austrian Empire. These historical processes have largely resulted in the emergence of two Ukraines.1

The Decline of Kiev & The Great Migration

Medieval Kievan Russia2 was a vast realm with immense wealth. Though bound by ties of oath and kinship to Kiev, the various constituent principalities enjoyed a great deal of independence, thanks to being spread out across the broad Eastern European plain. In spite of the geospatial obstacles to centralized authority, the Grand Princes of Kiev served as a central point of unity and were more than capable, when necessary, of corralling rebellious princes. While Kiev itself carried a great deal of cultural weight, its position and authority were largely the result of the vast wealth it acquired from the Dnieper trade routes to Constantinople. Kievan power reached its zenith during the eleventh century reign of Grand Prince Yaroslav the Wise, after which its power steadily declined.

Hoping to avoid a civil war upon his death, Yaroslav established a regulated system of succession in which every prince would receive an inheritance. The system, however, was overly complex and many of the lesser princes would not be content with their assigned lot. Upon his death in 1054 AD, Yaroslav’s descendants would spend the rest of the eleventh and twelfth centuries fighting amongst themselves.

While the Dnieper River basin served as the heartland of the united Russian realm, the infighting of the princes made it increasingly difficult for Kiev’s rulers to respond to nomadic raiding parties of the Kuman Federation. This led the region’s population to migrate in ever greater numbers to the principalities of northern Russia such as Novgorod, Vladimir and Suzdal. They also migrated, though to a lesser extent, west/southwest to Galicia and Volhynia, and northwest to Polotsk and Minsk. The migrations left Kiev less capable of defending against raids, which sped up the pace of migration - creating a sort of negative feedback loop. This in turn strengthened the positions of the other principalities, and bolstered their rulers’ claims to the throne in Kiev.

Prince Mstislav II of Volhynia seized the Kievan throne in 1157, precipitating its final decline. A carousel of princes seized the city and throne until it was finally sacked and burned by Prince Andrey Bogolyubski of Suzdal and Rostov in 1169. Bogolyubski proclaimed himself Grand Prince and moved the Russian capital to Vladimir.

Bololyubski’s decision was not unwarranted; the forests of Northern Russia were far more secure than the open steppe. The region between Muscovy and Vladimir had by now become the largest population center for the Russian people and had, along with the Republic of Novgorod, established profitable trading relations with Western Europe.

The Mongols and The Bifurcation of Russian Civilization

In 1221, a 20,000 strong Mongol reconnaissance force annihilated a 70,000 strong Georgian Army, removing the last barrier to Europe. The conquest of Russia began in 1237 with the sack of Ryazan and Vladimir. Chernigov was sacked and 1239, and a year later Kiev was all but wiped off the map. A Polish Catholic monk traveling through Kiev on his way to preach to the Mongols reported that the roads around Kiev were lined with Russian bones and no more than 200 homes remained in the city.3

The Mongol invasions sealed the bifurcation of power and population within the Russian realm and fundamentally redefined the power dynamics of Europe and the wider world. The realigned Russian principalities met the challenges of Mongol supremacy in fundamentally different ways. How they did so would have lasting implications.

The Northern Principalities: The Struggle for Orthodoxy & Autonomy

The Pope and Catholic rulers of Europe took full advantage of the weakening of northern Russia by the Mongols. Pope Honorius granted permission to the Swedish king in 1237 to launch a crusade against the “unbelievers,” sealing it with a wider Papal Bull in 1240.

Sailing up the Neva River, the Swedes were brought to battle and routed by the nineteen-year-old Prince of Novgorod, Alexander Yaroslavich. While this great victory secured him a place in history and the moniker Alexander of Neva, or Alexander Nevsky, it did not secure his position on the throne. The victory soured his relations with the boyars of his realm, who exiled him from Novgorod. But shortly thereafter, the crusaders of the Bishopric of Dorpat and Livonian Order captured the frontier city of Pskov in 1241. The Teutonic Order then joined the fray, expanding the crusader bridgehead and blockading Lake Peipus - crucial to Novgorod’s monopoly on the Karelian fur trade. Alexander was recalled, raising an army to liberate Pskov.

His army drove the crusaders from Pskov and pursued them deep into the German Bishopric itself, leading to one of the most famous battles in medieval Russian history: The Battle of the Lake.

After a small detachment of the Russian army had been defeated by Teutonic knights, Alexander reformed his forces on the straits of Lake Peipus to await the crusader army. Alexander concealed a sizeable force of allied Turkic horse-archers on his right flank, which he unleashed at the crucial moment of the battle, enveloping the crusader center. The exhausted crusaders were left with no option but to withdraw across the ice; but the April ice, unable to bear the weight of the German heavy cavalry, broke and hundreds of crusaders were plunged into the frigid waters, sinking to their deaths.

Alexander would spend the next few years repelling repeated attacks from forces of the Northern Crusade. Realizing that the Republic of Novgorod couldn’t survive in perpetual warfare, the great warrior-prince approached Batu Khan of the Golden Horde. Batu was well aware of Alexander’s exploits and respected him as a great warrior. He promised that if Novgorod would pay tribute to the Mongols the people would remain unmolested, and the independence and privileges of the Russian Church would be guaranteed. Alexander agreed. In time, Batu would appoint him as Grand Prince of Vladimir. This alliance helped the saintly prince to defend Northern Russia from repeated invasions from Catholic Sweden, Lithuania, and Germany, maintaining the purity of the Orthodox faith.4

Knowing that death was near, Grand Prince Alexander Nevsky took monastic vows and was tonsured into the Great Schema with the name Alexey. His passing was the cause of great mourning throughout Russia, and his veneration as a saint was almost immediate.

“My children, you should know that the sun of the Suzdalian land has set. There will never be another prince like him in the Suzdalian land.”

- Metropolitan Cyril, Second Pskovian Chronicle

The Rise of Galicia-Volhynia: The Struggle to Retain Independence

While the north was clearly emerging as the center of the Russian realm, it wasn’t the only center of power emerging from the fall of Kiev. On the western frontier with Hungary sat the important trading center of Halych (Галич or Galich, from which we derive Galicia), seat of the Principality of Galicia. To the north of Galicia, bordering the Kingdom of Poland, sat the principality of Volhynia. When the Galician prince died without an heir in 1199 his nobles invited Prince Roman the Great of Volhynia to rule. They believed Roman would be a largely absent ruler; instead, he moved his capital to Halych and united the two territories into a single realm, the Principality of Galicia-Volhynia.

Roman was a wise ruler and competent diplomat. He married the niece of the East Roman Emperor Alexios III, becoming the empire’s primary military ally against the Kuman Confederation. Having established peace with Hungary and allying his realm with Poland, Galicia-Volhynia’s star rose quickly. But peace with Poland broke down in 1205 and Roman was killed in battle. As a result, the kingdom was partitioned by Poland and Hungary, changing hands repeatedly for the next forty years. Fortunes changed once more in 1241, when Poland and Hungary were greatly weakened by a Mongol invasion. Shortly thereafter Roman’s son, Daniel of Galicia, defeated a combined Polish Hungarian army at the Battle of Yaroslav, retaking Galicia-Volhynia.

In spite of the immense chaos of the Mongol invasions Daniel’s reign would see Galicia-Volhynia reach the apex of its power, it would serve as a golden age of literature, culture, and art. Daniel’s reign also raises some interesting questions. In 1245 he crowned himself king, but in 1253 he was crowned King of Russia (Rex Russiae) by a legate of Pope Innocent IV, promising to promote recognition of the Pope in his territory. Daniel formed an alliance with Poland and Hungary, thus bringing Galicia-Volhynia into the Western, Catholic orbit.

How did this come about, considering this is well after the Great Schism and Sack of Constantinople?

At this time the Russian Church was a dependent of the Patriarch of Constantinople, but the Russians had largely ignored the schism, not quite believing that the Latins had fallen into heresy. This attitude quickly changed in the northern principalities as crusading armies repeatedly invaded Novgorod with the express purpose of converting the heathens - ie., the Orthodox. Things were different in the western principalities, due to their close proximity and growing ties to Catholic Poland and Hungary.

While the schism was initiated in the mid-eleventh century, it only really solidified with the Fourth Crusade’s Sack of Constantinople in 1204. What remained of the Roman military and intelligentsia regrouped at Nicaea. Pope Gregory IX had sent representatives to the court of the Roman Emperor, St. John III Vatatzes, in hopes of ending the schism, but these quickly broke down by the mid 1230s.5

The Mongol invasions renewed the Orthodox nation’s appetite for reconciliation with the West. In the wake of the Mongol sack of Chernigov and Kiev, Grand Prince Michael II had sought to secure marriage alliances with Poland and Hungary. When these failed Michael grew increasingly desperate for Western aid. But his Catholic neighbors could do no better. In addition to Poland and Hungary, the Latin “emperor of Constantinople” was routed, and his realm was on the verge of collapse. In 1244 the Mongols crushed the combined forces of Trebizond, Cilician Armenia, and the Sultanate of Rum at the Battle of Kose Dag - bringing the Mongols to the borders of St. John’s territory in Anatolia. As a result, St. John and Patriarch Manuel II of Constantinople sought a representative to send to the Papal court in hopes of reaching a compromise.

Metropolitan Joseph of Kiev had either fled or died during the Mongol invasion of Southern Russia, and this left Archbishop Peter of Belgorod as the interim head of the Russian Church. How the dialogue between the imperial court in Nicaea and Kiev came about is unclear. But what is clear is what Archbishop Peter was sent to the papal court as a representative of Patriarch Manuel II, on the orders of Grand Prince Michael II.

Archbishop Peter arrived at the papal court in the autumn of 1244. This episode, and his participation in the First Council of Lyon have been of key interest to scholars. There is virtually no mention of this in Eastern sources, but numerous Western manuscripts mention the presence of this Archbishop of Russia (archiepiscopus Russiae).6

Peter’s main task, or the information most of interest to the Pope, was his direct interactions with the Mongols. But the Annals of Burton provides other interesting details:

“Among other prelates of the world, the Russian archbishop named Peter arrived at the Council of Lyons. On return from the council, some participants stated that though he did not know Latin, Greek, or Hebrew, he brilliantly (peroptime) explained the Gospel before the Holy Father [the pope] through an [unnamed] interpreter. Being specially invited, he assisted in the Divine Service together with the Holy Father and other prelates, wearing sacred vestments [just as they did], but of different appearance.” - Annals of Burton7

This explanation of the Gospel would have been the recitation of the Nicene-Constantinopolitan Creed, as the Church always viewed its creed as the summation of the Gospel and its doctrines. The Pope and his prelates would’ve been interested to see how this Russian bishop interpreted the creed (with or without the Filioque) as an indicator of the Church of Russia, and by extension Constantinople’s readiness to compromise. That Peter was asked to concelebrate the Eucharist - forbidden to schismatics and heretics - is a strong indicator that the Emperor and Russian princes were willing to play ball in exchange for Western aid.8

While modern scholars, especially of the Catholic variety, like to point at this era as evidence that the Orthodox saw the Filioque and Papal Supremacy as mere political tools and not serious theological differences, this is misguided - as future events would prove. Instead, the East’ change in tone in this era is the result of a unique combination of theological, philosophical and dynastic developments coupled with political desperation. The twelfth to fourteenth centuries witnessed the rise of Scholasticism in the West and Byzantine Humanism in the East. It is no coincidence that the golden age of Galicia occurred in this time, running parallel with this last great flowering of culture and classical learning in Constantinople, known as the Palaiologan Renaissance.

While Byzantium was undergoing this great cultural revival it was also facing political collapse. They were clearly aware of Michael of Kiev and other Western Russian princes attempts to gain favor with the West, and it appears that as the emperors grew increasingly desperate to secure Western aid, they turned to a partner they knew could - and would, act as a mediator. As Fr. Meyendorff notes, while there were numerous short-term church unions over the course of the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, none of them had staying power as they were not a reconciliation of theological differences so much as a promise of ecclesiastical submission in exchange for secular salvation - a salvation which would never come.

This helps cast light on who sent Archbishop Peter to Rome, as well as Daniel’s crowning by the Pope and promises to spread commemoration of the Pope in his kingdom.

Daniel fully expected that the Pope would grant him an army along with his crown; this army, together with his Polish and Hungarian allies would wage an anti-Mongol Crusade to liberate Russia - a Russia which bowed the knee to Rome. But this was not to be - much to Daniel’s frustration.9 In spite of his best efforts to throw off the Mongol Yoke, Daniel, and the Kingdom of Russia (Королівство Русь) would remain vassals of the Khan; they would largely continue in their westward drift and evolve into a different, little Russia.

Roman sources of the time reveal that Constantinople felt Moscow and the northeastern princes were more aligned with their worldview and their cooperation became increasingly close throughout the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries. Simultaneously, the Romans grew increasingly suspicious of Galicia-Volhynia on account of the latter’s growing ties with the West.

Fr. John Meyendorff notes the following in his magisterial study Byzantium and the Rise of Russia":

“Those Orthodox countries which avoided facing direct conquest by the Crusades - Bulgaria, Serbia, and Galicia-Volhynia - were much more open to Western contacts and, all of them, even accepted (however briefly) the political overlordship of the Papacy. Here lies one of the keys to the understanding of the relations between Byzantium and Moscow in the fourteenth century, as opposed to the more cautious attitude of Orthodox Byzantium towards western Russian principalities of that period.”

- Meyendorff, John; Byzantium and the rise of Russia; p. 55

While Constantinople’s geopolitical power had waned, its cultural power was still immense. Russia’s Church was set up, broadly speaking, along the lines of those within Byzantium - with Russia being viewed as a province administratively. This worked well when Russia was a united whole, but as political divisions emerged, the princes would struggle for control of the Church.

The Struggle for the Russian Church

A deep rivalry had emerged between Vladimir-Suzdal and Galicia-Volhynia with both claiming to be the legitimate inheritors of Kievan authority. This contest now entered the ecclesial realm.

When the Metropolitan of Kiev died in 1308, King Yuri II Boleslav of Galicia-Volhynia nominated a zealous priestmonk living in isolation to fill the vacant Metropolis of Kiev. This zealous priestmonk, St. Peter of Moscow, beat out the nomination of Grand Prince Mikhail Yaroslavich of Vladimir and Tver, and was consecrated Metropolitan of Kiev and all Russia by Patriarch Athanasius in Constantinople. Due to Kiev’s depopulation, Peter quickly moved to Vladimir, and by 1316 Vladimir was established as the ruling See of the Russian Church.10

Ever since his election, Grand Prince Mikhail Yaroslavich had greatly resented St. Peter, even threatening his life in spite of the great prestige his relocation had afforded Mikhail’s realm. As a result, Ivan I, Prince of Moscow and grandson of St. Alexander Nevsky, offered St. Peter his protection if the latter relocated to Moscow; Saint Peter moved the ruling See from Vladimir to Moscow in 1325. From that moment on Moscow’s star was ascendent.11

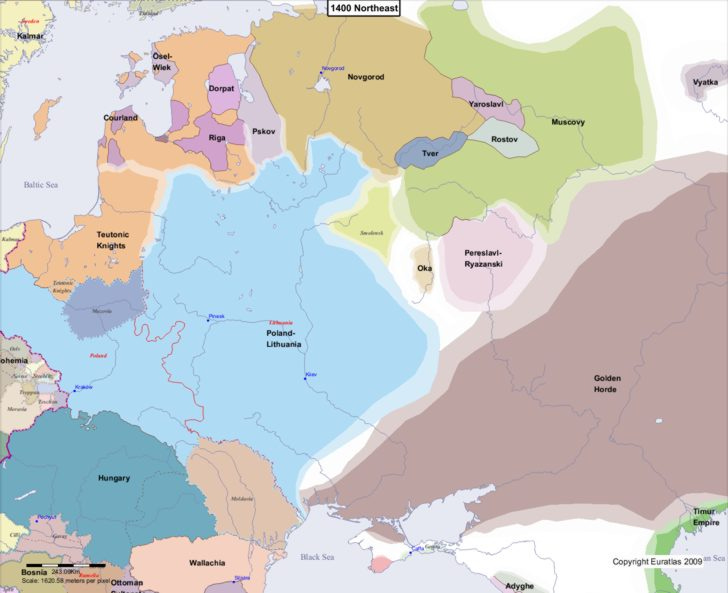

The Metropolitan’s move to Vladimir greatly alarmed the boyars of Galicia-Volhynia. They protested to Constantinople demanding that the Metropolitan be based in their territory. Initially, Constantinople declined, having grown increasingly suspicious that the Galicians were too heavily influenced by the Catholic powers along their borders. Things would become even more complicated a joint Polish-Hungarian army invaded and annexed Galicia-Volhynia in 1349. Poland received Galicia and western Volhynia, while Lithuania annexed eastern Volhynia, Turov and Kiev.12

The political divisions of the Russian Metropolis forced Constantinople to make concessions to the rulers of Lithuania and Poland. With the death of Metropolitan Theognostus of Moscow, Grand Prince Olgerd of Lithuania sent a monk named Romanos of Tver to Constantinople. Olgerd wanted his preferred candidate to not only be enthroned Metropolitan but to reside in Kiev under his political leadership. But Romanos arrived in Constantinople after St. Alexis had already been consecrated Metropolitan of Russia.13 As a consolation, Romanos was consecrated Metropolitan of Lithuania-Volhynia in hopes of Lithuania’s conversion. But Olgerd did not keep his word, and upon Romanos’ death in 1362, Lithuania-Volhynia was administered by St. Alexis in Moscow it was dissolved back into his Metropolis of Russia in 1371.

An even greater crisis emerged however, that very same year. The Polish King Casimir (III) the Great threatened to forcibly convert his Russian Orthodox subjects to Roman Catholicism if he were not given a metropolis of his own. Patriarch Phliotheus I of Constantinople elevated bishop Antoniy of Halych to the rank of Metropolitan of Halych, granting him Kholm, Turov, Peremyshl, and Vladimir-Volhynia in what is today western Ukraine and southern Belarus.14

The result was that, during the fourteenth century, Constantinople had two Russian Metropolises, the original Metropolis of Russia now residing in Moscow, and others which periodically represented western Russian communities subjected to heterodox rulers. In order to easily distinguish between the two ecclesiastical territories, Moscow became known as Great Russia or Major Russia, while what had been Galicia-Volhynia become known as Little Russia or Minor Russia - Malorussia. 15

Little Russia: The Use - And False Controversy

By no later than 1334, Yuri Boleslav, King of Galicia-Volhynia, had begun to sign all of his decrees “Natus dux totius Russiæ minoris,” or roughly, Born Ruler of Little Russia. Polish and Lithuanian rulers, both local rulers up to the kings and grand dukes would do the same. Vladislaus II of Opole, who held Galicia beginning in 1371, held the title Lord of Russia (Terre Russie Domin). Thus, from the early fourteenth century, the land and its people were known as Little Russia, or Malorussia, and Malorussians. This would not begin to change until the Union of Brest, and the later advent of a distinct Ukrainian identity in the mid to late nineteenth century.16 17

We can, therefore, put to rest the baseless claims of many popular historians who claim any mention of Little Russia to be a product of Russian Imperial propaganda and a denial of the people’s history. As we will see in subsequent centuries, the region's inhabitants will identify themselves and their lands with this term. It will become a sort of rallying cry for those seeking to preserve their culture, heritage, and religious convictions in the midst of homogenization campaigns from the Catholic kingdoms who will come to rule them.

Conclusions

The migration of nomadic peoples across the steppes was a recurring challenge which the settled civilizations of Europe and the Near East seemed incapable of meeting head on. Unable to band together to drive off the threat, the persistent raids by Pechenegs and Kumans resulted in a weakened Russian center just at the time when its greatest challenger, the Mongol Horde, was moving across the vast expanse of Asia. This led to the bifurcation of Russian civilization.

While the move northeast assured perhaps an extended period of Mongol vassalage, the Mongols were tolerant of the Russian’s Orthodox faith and largely avoided interfering with their affairs so long as they paid tribute and sought approval for the elevation of rulers. By contrast, the Catholic powers of central and northern Europe were unwilling to tolerate the “schismatic” Orthodox among their neighbors and subjects and actively sought their conversion (first through diplomatic efforts, and later by force) beginning no later than the thirteenth century. Western Russian nobles were, by and large, willing to compromise with the Catholics if it meant retaining power and privilege.

Whereas the northern principalities centered on Moscow placed purity of faith over and above political self-determination, those centered on Galicia placed political self-determination over and above purity of faith.

We can see then a clear divergence in the hierarchy of values of Malorussian nobles compared to the rest of Russia. The reason for this change lies in a weakening of the Orthodox Faith and Worldview among the political and clerical elites of Malorussia after generations of exposure to secularizing ways of thought and political subjugation to Catholic rule. We will see this trend continue among the Malorussian nobility, notably during the fallout from the Union of Florence. While the majority of the Russian Church rejected Florence and broke communion with Constantinople, Malorussian churchmen chose to remain under a Unionist Patriarch of Constantinople, forming a separate papal-approved Metropolis of Kiev. Although the Union would not last long, the seeds of separation had been sewn.

The next several centuries would mark an immense struggle for the very soul of the western Russian people, and the bifurcation of their population into two subsets: one which would submit to Rome in hopes of gaining political equality to preserve their cultural identity; and another which located the source of their cultural identity in the preservation of their Orthodox faith - the landmarks left by their fathers. From this latter group, many young men would flee south and build new communities where they could preserve their faith and customs. The lands they entered were largely lawless, Tatar and bandit-ridden outlands known as the Ѹкраина, or The Ukraine.

Kievan Rus was the medieval state from which the peoples of Russia, Belarus, and Ukraine originated. Its Varangian (Eastern Viking) chieftain, Rurik, would lend his name to the founding dynasty, which lasted through St. Vladimir the Great and the Baptism of Rus in Kiev, all the way to Tsar Ivan Grozny (The Terrible) in Muscovy.

Ruthenian, and Rusyn, are simply Latinizations of Russian. Even Russophobic historians, such as Norman Davies in his Vanished Kingdoms, are forced to admit this reality. Thus, I have chosen to simply use Russian, as it is the etymologically correct term - if politically incorrect for our Uniate friends in post-Maidan Lviv.

Modern scholars often call such claims into question, but the Mongols had a reputation for razing cities to the ground. Even if the account is an exaggeration - which is not self-evident, it tells of the sheer scope of destruction.

Duffy, James P, and Vincent L Ricci. Czars: Russia’s Rulers for over One Thousand Years. New York, Barnes & Noble Books, 2002, pp 62-64

This dialogue produced the Disputatio with the Latins. This important text has recently been translated into English by Liverpool University Press

Or as his name and title are rendered in the Linz Code, “Petrus archiepiscopus de Belgrab in Ruscia,” or Peter Archbishop of Belgorod in Russia.

MAIOROV, ALEXANDER V. “The Rus Archbishop Peter at the First Council of Lyon.” The Journal of Ecclesiastical History, vol. 71, no. 1, 5 Nov. 2019, pp. 20–39

H.R. Luard, ed., Annales monastici. Rolls Series 36. 5 vols. (London: Longmans, 1864–9), 1: 272

Maiorov, Alexander V. “A Medieval Effort toward Unity: Latins, Greeks, Russians and the Mongol Khan.” Journal of Medieval History, vol. 49, no. 4, 9 July 2023, pp. 495–515

The Rus Archbishop Peter at the First Council of Lyon, Alexander V. Maiorov; Journal of Ecclesiastical History, Volume 71, No. 1, pages 20-39, Cambridge University Press, 2019

Saunders, John J. The History of the Mongol Conquests. Philadelphia, Pa. University of Pennsylvania Press, 2001. p. 101

As there was only one Metropolitan in all of the Russian lands, the title remained Metropolitan of Kiev and All Russia for some time, in spite of their residency elsewhere.

It should be noted that this move from Vladimir to Moscow was carried out with the blessing of the Roman Emperor and Patriarch of Constantinople.

With the fall of Roman and Daniel’s dynasty, King Casimir of Poland took on the title of Dominus Terrae Russiae, Lord of the Land of Russia. But it was Lithuania who really benefited, and would come to take on an increasing number of Russian lands. As early as 1265, 300 Lithuanian nobles were baptized into the Orthodox Church. By the time of St. Peter of Moscow’s episcopacy, it was said that there were two Russian capitals: Moscow and the Lithuanian capital of Vilnu (modern day Vilnius).

Up until this time, there was no such title of Metrpolitan of Kiev. Until the time of Yaroslav the Wise, Russia was seen as a missionary territory; The piety of Yaroslav and the security of his reign convinced the Romans to appoint a metropolitan to the Russians. Its administration was set up in line with Canon 34 of the Apostolic Canons. In other words, it was set up a Roman province in Barbarian lands. In such cases, the Metropolitan is not the prelate of a provincial capital who further acts in primacy over other bishops throughout the province, but the sole provincial authority with multiple individual sees. For example, Maximus of Kiev took on Vladimir-on-the-Klyazma without renouncing his episcopal authority of Kiev. St. Peter of Moscow had three personal cathedrals in Russia: Kiev, Moscow, and Vilnu. He had two vicar bishops who held his seat in Kiev and Vilnu while he was in Moscow and abroad.

For more information, see Meyendorff, John. Byzantium and the Rise of Russia : A Study of Byzantino-Russian Relations in the Fourteenth Century. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2010, p. 74-77

Majeska, George P. Russian Travelers to Constantinople in the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Centuries. Washington (D.C.), Dumbarton Oaks Research Library And Collection, 1984. Chapter 13

There are those who claim that a Metropolitan of Halych was founded as early as 1303 in response to St. Maximos of Kiev moving to Vladimir at the command of the Mother of God, that a certain Niphon served as Metropolitan of Halych for two years, and that the seat lay vacant, with each consecutive Metropolitan of Kiev (residing in Vladimir and Moscow) serving as the “effective administrator” of the Metropolis with several ahistorical persons filling the seat for a year or two here and there. But there is minimal, if any historical evidence for any of this, and any references online articles make are to modern text with no period sources - mind you, there are plenteous contemporary witnesses for the Metropolitan of Kiev in Vladimir and Moscow.

Ефименко, А.Я. История украинского народа. К., "Лыбедь", 1990, стр. 87.

Majeska, George P. Russian Travelers to Constantinople in the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Centuries. Washington (D.C.), Dumbarton Oaks Research Library And Collection, 1984. Chapter 13

The earliest use of this term was in 1298AD in the Greek: μικρὰ Ρωσσία, or Minor Russia. See: Codex Kodinos

KOHUT, ZENON; The Development of a Little Russian Identity and Ukrainian Nationbuilding. Harvard Ukrainian Studies, vol. 10, no. 3/4, 1986, pp. 559–76.

This is an impressive historical summary, Ben. I appreciate the thorough use of cited sources. This has been a humbling read which has prompted me to add some of these texts you've cited to my ever-growing Orthodox reading list for further study at a later date.

You're spot on in stating that most Americans are disinterested in history. There is something of a subconscious (and sometimes not so subconscious) social consensus here in the contemporary United States which views everything that occurred prior to 1775 as something of a moot point, with a few exceptions (see: the recent social media trends relating to modern Western man's interest in the Roman Empire).

This ill-informed sensibility has been paired with decades of neoliberal/neoconservative information inundation. The result being a modern American population which is largely incapable of viewing contemporary issues in their complete historical context. This incapability, when paired with the passions (pride, vanity, etc.) - results in the widespread support of disastrous domestic and foreign policy initiatives.

I look forward to reading Part II(A) when I have the time. Thanks for your efforts here.

Thank you so much for this extensive history of the Kiev Rus. It will take some time to digest, ⚔️🛡️🏰🐎 your footnotes are excellent, THANK YOU! 🌐 🔔 ☦️ ⛪